Cheng’s music career crescendos at Carnegie Hall

KATIE KIM//USED WITH PERMISSION

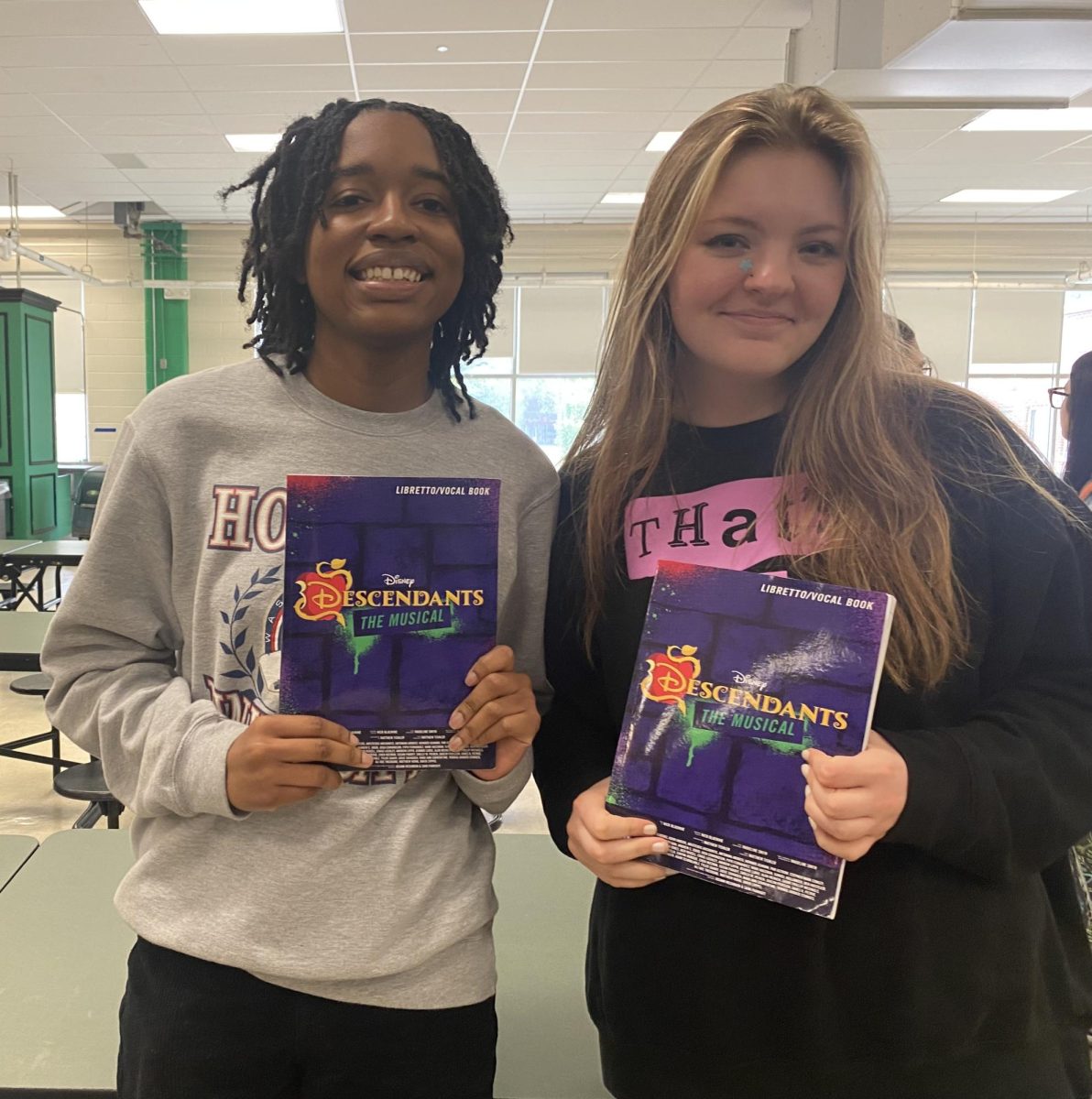

Jason Noble conducts a rehearsal for the Honors Instrumental Performance on Feb. 3, a day before the concert. Because each instrumentalist learned their piece individually, these intense practices were crucial to perfecting the music before the performance.

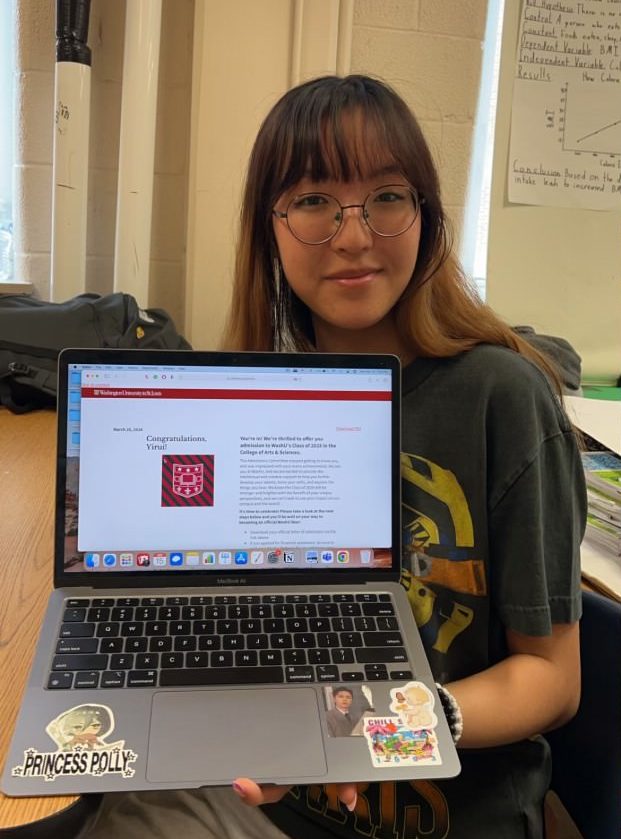

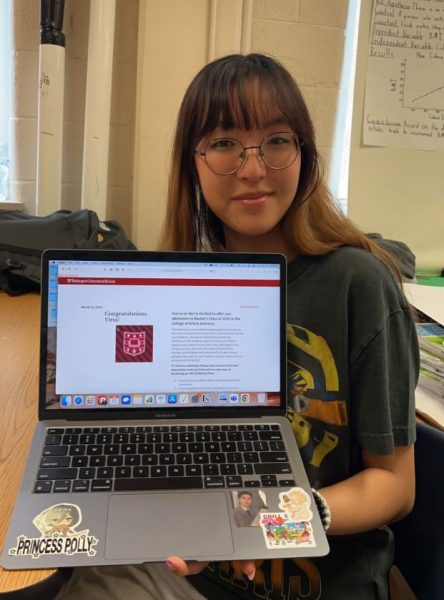

(CATHERINE CHENG//USED WITH PERMISSION)

What do Tchaikovsky, The Beatles and Catherine Cheng (10) have in common? These three — and many more — musical entities hold the world-recognized honor of taking the stage at Carnegie Hall. Since its construction in 1889, Carnegie Hall was originally home to the Oratorio Society of New York and the New York Symphony Society. Over time, the Hall opened its stage to a massive array of talents, including high school musicians selected for their talent in an Honors Orchestra.

Though flute has clearly prevailed as her top choice in instrument, Cheng’s exposure to producing music began much earlier. Through experience in piano and violin, Cheng learned basic musicality and performance skills.

“I started in seventh grade and before that I played the piano and the violin … my parents were like ‘You have to choose one instrument,’ and I really didn’t like the violin,” Cheng said. “My friend was playing the flute, and she was really good at it, and she really liked it, so she said she could introduce me to her teacher.”

Like many other instruments, the tone and mood produced by a flute can be heavily influenced by the musician’s choices. Cheng observes this while learning each new piece, and works to infuse her own touch — which proves to be more time consuming and harder to navigate.

“I’d say learning it and getting the fingerings down depends on how hard it is,” Cheng said. “I think putting music and expression into it and perfecting it is harder. Because with fingerings, it’s written on the page and you just do it, but with expression and style, I don’t know what to do. If I’m stuck and I don’t like how I sound, I have to really think how I want to make that better and how to make myself like what I’m playing.”

Like any other hobby, Cheng enjoys moments of quick understanding and ecstasy that can sometimes be contrasted by various obstacles. Unlike some musicians, Cheng was able to garner precious experience that made stage fright almost nonexistent. For complex pieces, Cheng has devised a system to help her overcome some technical or skill-based challenges.

“Stage fright was never that big [of a deal] for me because I did piano before it, and I did competitions with that, so I was kinda used to performing,” Cheng said. “But when I’m learning a piece … if it’s a difficult piece, and I’ll take it very slow and make sure I’m consistent before I try to make it faster and on tempo.”

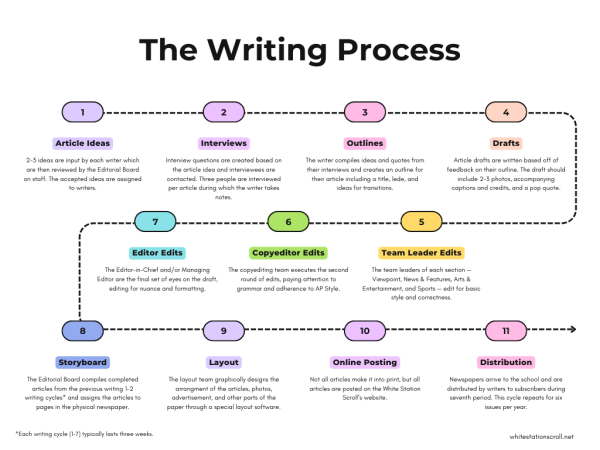

As Cheng took advantage of multiple competition and showcase experiences provided by her teacher, she eventually came across the opportunity to virtually audition for the Honors Instrumental Performance, a showcase of excellent high school musicians held in Carnegie Hall. Each musician learned their part individually, then arrived in New York City ready to collaborate with fellow talents and prepare for the performance.

“We practiced before, about two or three days [with] 10 hour rehearsals each day,” Cheng said. “The concert was really cool. It was really fun playing with people who all loved what they were doing.”

Compared to venues Cheng had performed at previously, Carnegie Hall’s acoustics were notably more sensitive to sound. Individual awareness became key as Cheng quickly had to adapt to the new setting.

“I had to make sure that I sounded good because sound bounces everywhere and it’s fuller there,” Cheng said. “I had to focus on making my tone fuller, and I had to focus on making myself blend better with everyone else.”

For Cheng, hearing the symphonic orchestra playing in harmony was joyful and satisfying. As she points out, it is often difficult to understand the full breadth of a musical composition without all its parts present.

“When I’m practicing by myself for a piece before [hearing] the whole orchestra, I really don’t know what it sounds like unless I’m playing with the recording,” Cheng said. “Most of the time I’ll just play my own part and it sounds kind of bare … once you put it together you hear it for the first time and with the whole orchestra it’s really nice because it’s like, ‘This is music.’”

Beyond the memorable experiences gifted to Cheng through playing the flute, making a connection with this instrument has impacted her personal life in a way different from her previous musical endeavors. For Cheng, this influence has been indispensable as she reaps the personal benefits of a consistent hobby and discipline.

“Honestly, it’s made me more productive because instead of just sitting at home and lazing around in bed until 8 [p.m.], I can get up and get something done,” Cheng said. “It was kinda different because with piano and violin; I didn’t really like them and I actually like playing the flute.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of White Station High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.