New cafeteria management promises better, healthier school lunches

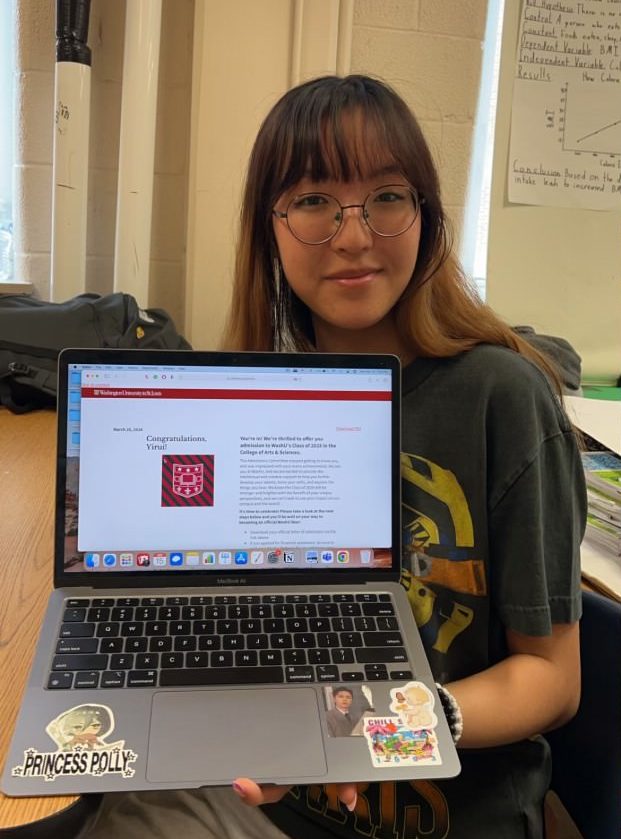

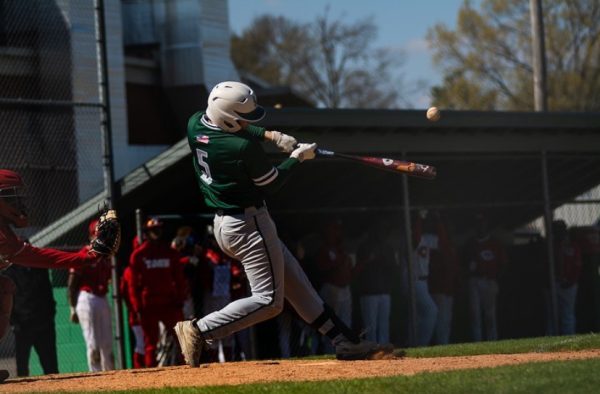

The newly merged SCS plans to be the first district in the nation to offer three free meals a day. They also plan to offer healthier options. Marcus Rhodes (12) chooses to supplement his lunch with fruit.

Mystery meats, runny slop, and rancid milk cartons are the classic images of cafeteria food. It is a commonly accepted fact of a life: a gourmet meal can’t be bought in a lunchroom. But ask the new food initiative team for Shelby County Schools, and you will hear a different story.

Starting next year, all meals at every school in the district will be free. Shelby County Schools will be the first school system in the nation with a universal meal plan.

For students, food will not only be free, but it will also be higher quality, healthier, and tastier.

Nutrition is now at the top of the Shelby County School agenda. Recent statistics reveal that 86 percent of Memphis public school students qualify for free or reduced lunch, making nearly every previous city school a Title I school. To the merging school systems, these are facts that cannot be ignored. Schools have both an opportunity and an obligation to ensure that kids eat the best food money can provide.

“Most of the previous Memphis City Schools kids ate their best, and sometimes only, meals of the day in their school cafeteria.” said Ben Townsend, a farm and nutrition educator for the school district.

With 150,000 mouths to feed daily, shifting the meal plans for one of the largest school systems in the nation is no easy task. The first step was hiring Chef Tony Geraci, a nationally recognized “Cafeteria Man.”

Before being recruited to Memphis, Geraci revolutionized lunchrooms for the 83,000 students of Baltimore City Public Schools. He integrated local, non-processed, fresh foods into the meal plan, surveying students first to make sure it was all what they wanted to eat. He turned 33 acres of decaying, urban landscape into an organic “Great Kids” farm. Geraci worked with Michelle Obama and Michael Pollan to get the best food he could possibly find. Now in Memphis, he has similar plans.

One of Geraci’s first steps is providing the school system with local foods. In Baltimore, he bought $2.3 million worth of local peaches each year. This year he has already purchased bulk produce from several local farms, including Harris Farms and Jones Orchard.

Geraci also implemented free breakfast for the remaining city schools that did not offer it. In many elementary schools, bagged breakfasts are now passed out in classrooms.

“My job is to put healthy kids in front of educators so they can learn.” Says Geraci, who believes providing three meals is essential in schools where many students may not eat when they go home. This led him to create after school dinner programs in many schools.

Geraci has hired a team of local farmers to help out with student-run gardens throughout Memphis. At Grahamwood Elementary, full-time farmer Lauren Bangasser oversees a massive demonstration garden. Schools will soon incorporate herbs and produce from the gardens into their cafeteria lunches, and kids who volunteer in the gardens will be able to take some of the yield home for their families.

Townsend explains the driving force behind all of these nutritional changes.

“We hope to give Shelby County students the best food we possibly can.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of White Station High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.