Counselor Change

Located at the heart of the second floor of the East Annex, students in 10th-12th grade were assigned counselors based on their last names; however, this year, some students’ counselors are different. Now organized by grade level, Leslie Fleming and Heather Heaston work with seniors, Stefanie McClain with juniors and Tamala Brown-Malone with sophomores.

“I just found out … about the counselor change … during the grade-level meeting,” Audrey Webb (12) said. “I wish they were more communicative about [the counselor change], but I don’t mind it because Ms. Fleming is really nice. It is weird having a new counselor who doesn’t know me that well … I don’t mind it too much, though, but going into my senior year, I would prefer someone who knows me well.”

White Station was one of the remaining schools in the Memphis area that organized students by last name, but this change has enabled counselors to better specialize in their respective grade levels. For example, Fleming and Heaston can focus on college admissions for seniors, while McClain can focus on standardized testing for juniors. Although this transition was unexpected, according to Carrye Holland, the school’s principal, it was not made quickly.

”I really love doing things that help all students,” Holland said. “So any time I make a change, I am never gonna mak[e] a change that affects students without thinking through it. It doesn’t mean it’s going to work, it doesn’t mean it’s always going to be perfect or great, but it took me years to make this counseling shift because I want[ed] to make sure that it was something that I could support, sustain, make sense of [and] that checked all of the boxes for student success. It may fall flat. You don’t know until you get in and try it but I needed to have a lot of things in place before I finally ripped the Band-Aid off.”

Some students are worried about the impact of the counselor shift, especially those who rely on them for support beyond the classroom. This support can include academic, behavioral and social, which can improve a student’s experience at White Station High School.

“Since we had the counselors for so long, we got to know them, [and] they kinda got to know us, especially if you had a lot of interactions with them … they [could] talk about more stuff [in the counselor recommendation],” Webb said. “But if you have a new counselor every year, you are not able to get close to one and get them to know you. I think it would be hard, especially if you had to deal with them for non-academic stuff … and you have to do the process all over again … So I think it would hinder somebody who really relies on the counselor [even outside of academics].”

Although no one knows exactly how the counselor shift will play out, administration did consider the different variables by looking at other schools before making the change. Moving forward, student proactivity will also play a role in developing a potentially new relationship with a different counselor, making up for their lost time and getting to know their new counselor.

“I think that the kids that sought counselor support before are going to be advocates for themselves and come and say, ‘Hey, who’s my new counselor; what’s going on; what are we doing?’” Holland said. “Whether it was going to be last year, this year, next year, somebody was going to be affected … Let’s see what happens [with this counselor change].”

Academic Advisory

With roughly 25 students in each advisory group, this new advisory program serves as a “check-up” space where students can connect with their peers twice a week to discuss various topics about school — ranging from the college admission process to what is being offered on campus. Written by this year’s new Optional School Coordinator, Destin DeMarco, the advisory program is based on the curriculum from Facing History and Ourselves and other online resources. All advisory groups, regardless of grade, will be following the same curriculum for the first month; however, each grade level will soon branch off and follow a specialized curriculum tailored to their specific grade level. Advisory aims to cater to students who are unsure of what they want to do or lack a solid support system.

“I think students who are looking to be connected to something [could benefit from academic advisory],” Holland said. “But I also think [that] even students who [do not feel disconnected] can benefit because they can help somebody else … I think everybody in a room can either bring something, take something or both.”

Prior to academic advisory, students would tune into watching RethinkEd’s Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) videos every Tuesday. Whether it was through watching the videos or conversing about the activities with the class, some students did not feel like SEL was properly addressing their social and emotional needs.

“SEL was not efficient at all,” Webb said. “It really was a waste of time … especially since [most] of my teachers did[n’t do] it. I felt like [SEL] was so basic [and vague] … I think it would be better if [academic advisory uses] a different format [compared to SEL] … I think student-opinionated feedback would be very important. I feel like if they don’t take that, it’s going to be a huge bust.”

Holland emphasized that academic advisory is not like a study hall but rather an environment where students can connect and discuss all things relating to academia or their lives outside of school. Teachers also have the option to check in or have a one-on-one conversation with their students to discuss their grades, attendance or life at home. On the first day of academic advisory, teachers were handed a rough itinerary of how to conduct advisory; however, some teachers, like Dwight Wade, the ninth grade English CLUE teacher, opened this conversation with the students.

“I asked the kids … ‘What do you want out of [academic advisory?]’ and the students said, ‘Well, we want to go outside,’” Wade said. “[While] walking back from Walgreens … I noticed a lot of trash around … [and] I found that when I pick up trash, what I am really doing is practicing the principle of leaving the world a better place than I found it … It just bleeds into over everything I do, and I said [to the students], ‘I think that is a good idea … If you want, we’ll pick up trash, and we can sort of experiment and see if this doesn’t help us grow as individuals and help us develop our improved capacity to become members of a group — a community.’ If we can help develop this ethic of leaving every day, every person, every moment a better place than where we found it [we’ll have succeeded].”

Although White Station’s curriculum is inspired by other schools around the U.S. that have similar programs, monitoring is a must to see how students and faculty adjust to this new program.

“I have thought a lot about what I want advisory to look like and what I want it to do, and try to build that vision with teachers,” Holland said. “Will it ever truly be standardized? No, because teaching is not [the same from person to person] … Anyone [who] understands teaching, knows that when you teach, when you guide, when you instruct, when you facilitate, [these] are [all] very nebulous things … I would like to see what each teacher does, and at some point, I will ask students about their experiences, just like [how students] have perception surveys about teachers.”

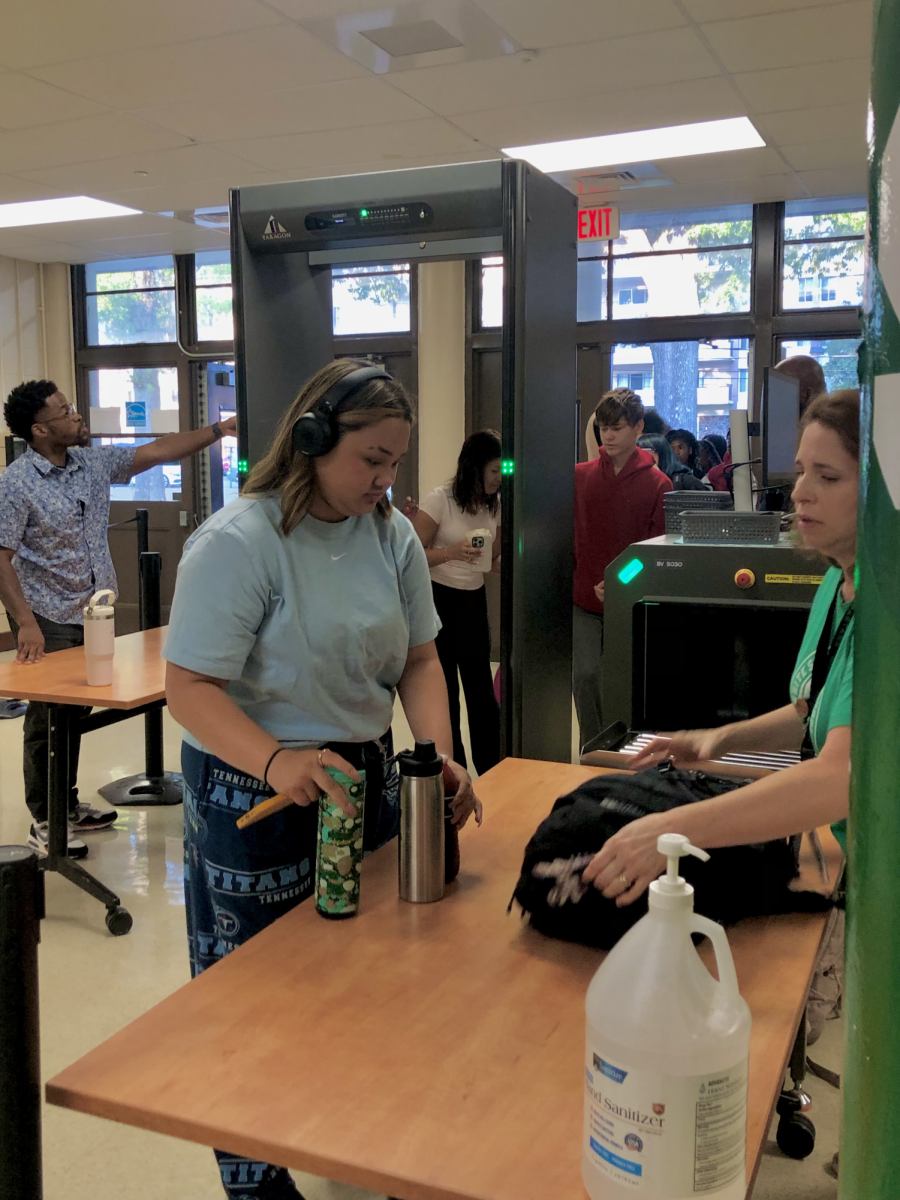

Morning Metal Detectors

With growing concerns surrounding safety on campus, the school has invested in new equipment including security cameras and a weapon detection machine. Previously, metal detection was conducted infrequently, and fewer precautions were taken compared to this year. Now, when students walk through the doors in the morning, they place their backpacks and lunchboxes on the conveyor belt and walk through the metal detector.

“I think opening more entrances is great, I think that will definitely help [streamline the whole process], but it’s also [not] like they are making every single person go through [the metal detectors],” Webb said. “Like today … there were two people in front of me [about to go through] the metal detectors, and the officer … just told me to go [to class] … Even if they [made every student go through the metal detectors], that would be wildly inefficient, like you would have to block off 30 minutes every day to have every single person go through the metal detector. So it’s not perfect, but I think [that administration is] definitely trying, and I understand their concern [about safety], but it’s also like, I don’t know how else we would do it.”

Even with new equipment and more staff at their duty posts, it is still a tall order for any place to have the utmost security, especially with all of the possibilities that could happen with thousands of people roaming around campus.

“I have never truly felt unsafe in this building as the principal or an administrator, but I am also not a student or a teacher who doesn’t have access to all of the information that I have,” Holland said. “But I constantly think about how students feel, how teachers feel, how parents feel about their children being at school … [but] you can’t control every variable … there is no way to have ultimate safety, but you can do a lot of things beyond just metal detectors.”

Aesthetic Changes Around the Station

Although lined with cinder blocks and green lockers, Holland believes aesthetics play a key role in creating a positive learning environment — something more like a college atmosphere. An example would be the renovated spaces in the Career and Technical Education (CTE) courses, made possible by expanded funding, such as the addition of a new nursing lab.

“I’m a big believer in spaces and how they reflect how you respect, treat or behave,” Holland said. “[For example,] the courtyard, the obstacle course out back, the garden, just trying to come up with ways to have little spaces … [I’m] just trying to improve spaces where kids can think about their future.”

There are ongoing projects beyond the recent library changes. The renovation of the courtyard, for instance, was a small but significant project that took around two years to plan, fund and complete.

“I want to prove that people love White Station, that people believe in public education, still believe in White Station [and] that alumni are still invested in their school,” Holland said. “It was an experiment to prove whether [or not] people would put private funds into public schools because a lot of people feel like the public school system should sustain itself … Tax dollars are not going to pay for aesthetic spaces like … pretty courtyards … It’s a long, very tedious process.”