No oil in our soil: the student battle against the Byhalia Pipeline

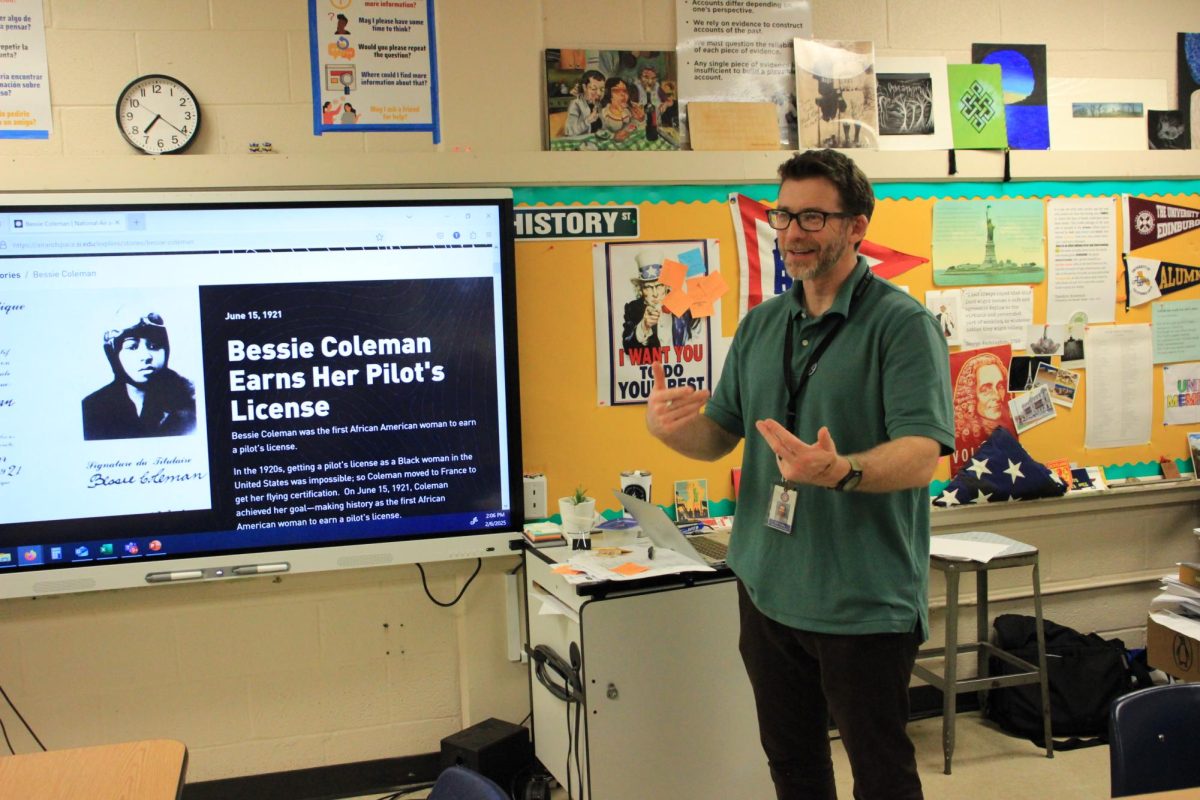

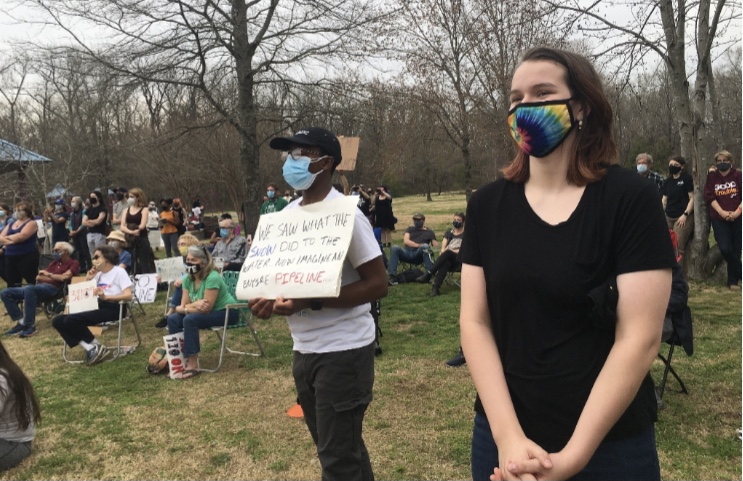

Student protestors William Smith (12) and Ellen Barnes (12) engaged at a protest on March 14, in attendance with figures such as Al Gore. Their sign detailed the slogan, “We saw what the snow did to the water. Now imagine an entire pipeline.”

From Feb. 18-25, Memphis was under a boil water advisory. Almost all water used had to be boiled or bottled, for activities from cooking to brushing teeth. The Byhalia Pipeline, a transport line for oil to make its way out of the country, would make this a common reality for people in Memphis.

“Luckily, we only experienced something that was short-term, but when I think of the consequences that could come from the pipeline being here, it reminds me of the Flint, Michigan water crisis,” Ellen Barnes (12) said.

Much like the water crisis in Flint, the Byhalia Pipeline would affect neighborhoods of color far more than the whiter, wealthier, suburbs.

“It’s supposed to be built under the Boxtown community, South Memphis … It curves around just the white communities such as Germantown and Collierville communities,” Barnes said.

The pipeline, coined by former Vice President Al Gore as a “reckless, racist, rip-off,” has its origins in two Texas companies seeking “the path of least resistance.”

“It’s running through predominantly black neighborhoods, and the company said that that was the path of least resistance,” William Smith (12) said. “Although it may not be intentionally, that’s the reality. [Environmental racism is] systemic racism; that’s what it’s all about.”

The oil companies behind the Byhalia Pipeline have several tactics lined up to secure the necessary land, ranging from manipulation to a modicum of money.

“One family has a plot of land that they want; they want to put the pipeline straight through it,” Barnes said. “The company kept sending more and more people and offered up to $11,000 basically trying to predict what their land is worth without even thinking about the sentimental value that it holds to that family.”

For Memphians, the outcome will be determined at a more local level, with state legislators choosing to remain uninvolved in the fray.

“The state replied to this whole situation by saying ‘It’s not our problem, you guys deal with it,’ so now it’s up to Shelby County,” Barnes said.

Students like Barnes and Smith attended a March 14 protest, with the White Station High Environmental Alliance rallying to host their own in the future.

“We can protest and rally against it, like the one on Sunday … definitely rallying together to support this cause is important,” Smith said.

The student body — including those who are less inclined towards displays or uninformed — has the power to help put forth change beyond protests as well.

“Contact our local city council and our state commissioners because they are going to be the ones voting to give the pipeline a permit,” Smith said.

Even voting will not necessarily be enough to deter the pipeline; it is expected that legal action will follow, attempting to force the pipeline for profit.

“They’re arguing on the basis of eminent domain,” Barnes said. “They’re trying to say the land isn’t really theirs and trying to work the state laws [in their favor].”

With Memphis City Council having denied the pipeline access to Boxtown in a March 16 vote, the next steps include seeking federal assistance and a continuation of the protests already in action.

“There’s more things happening for climate change in general. I’m helping organize a protest that will take place on Earth Day,” Barnes said. “It’s not focused on the Byhalia Pipeline, but it’s another opportunity to listen to speakers in the community.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of White Station High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.