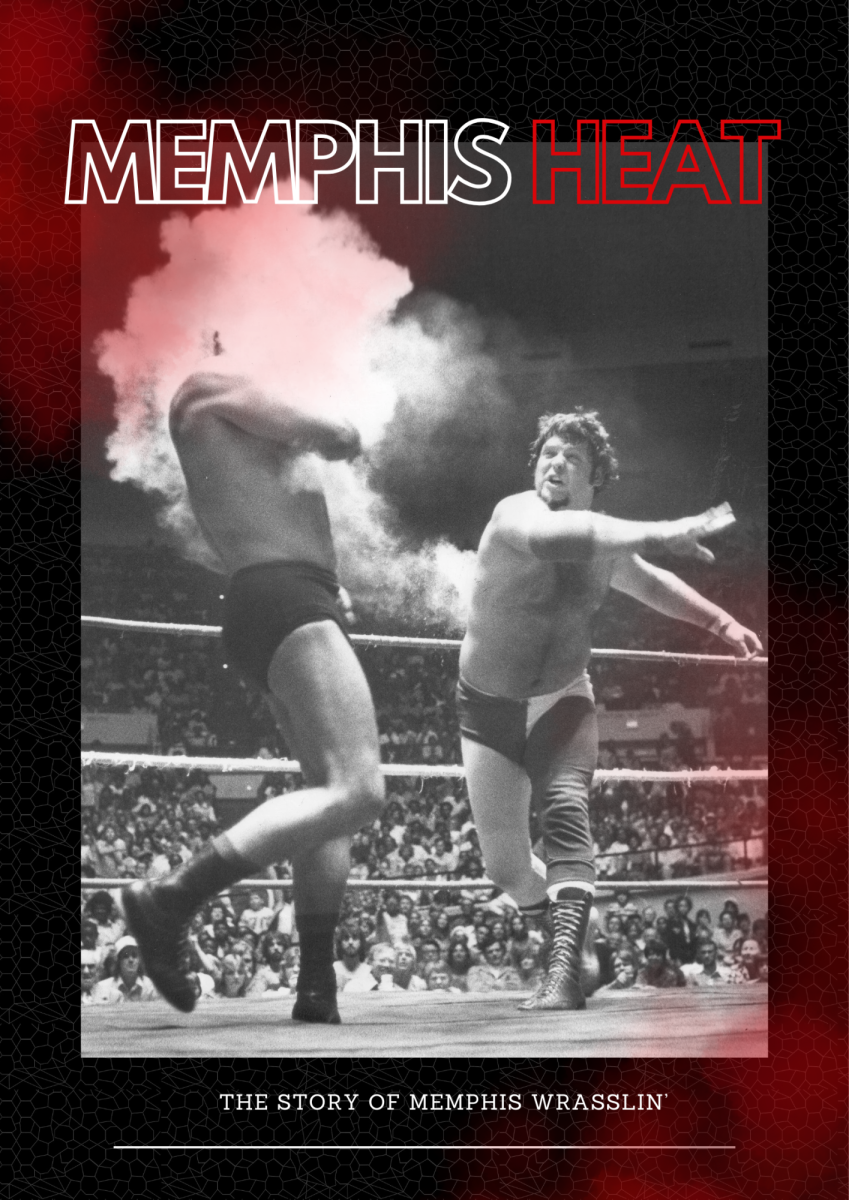

Ten thousand fans filled the Mid-South Coliseum every Monday night to see “The King,” screaming for blood. Thousands more tuned in every Saturday morning to watch him win, eyes glued to the chaos. But this was no Elvis Presley — it was Memphis wrestling, where good and evil brawled through the aisles, where legends were made in concession stand fights and where one man became King, not by birthright, but by sheer force of will. Jerry “The King” Lawler did just that, and his kingdom reigned through the Mid-South with Memphis at its pinnacle.

Show wrestling traces its roots back to the carnival days when a “tough guy” would challenge audience members to win a cash prize — only for a hidden enforcer behind the curtain to ensure no one ever collected. While real wrestling is the foundation for every match, when the showmanship of wrestling matches popularized in the 1950s, the true popularity lay in the drama and illusion created by the wrestlers themselves.

Original professional wrestlers like Jackie Fargo, one of the first wrestlers to introduce trash-talking, and Sputnik Monroe, a civil rights activist who pushed for integrated crowds, played a key role in what became one of the most long-running and intense cultural phenomena of the Mid-South — professional wrestling.

“These guys weren’t gonna become famous movie stars … but they were rough … you wouldn’t have wanted to get in a fight with them,” Russel Wiener said. “You knew it was totally fake, but it didn’t really matter … these guys were not, you know, the sharpest … but there was something a little bit dangerous about it.”

In the late 1960s, there was a shift in the wrestling world. Territories were built, and wrestlers began to travel upwards of 600 miles a night before they reached their next territory. As a cycle of travel, fight, film and repeat began to take shape, the energy surrounding the wrestling world grew.

“These wrestlers would travel around … wrestling in high school gymnasiums or whatever … and then they’d film some of that just to hype up [their matches] … and that was what really got people into it,” Wiener said.

Every Monday night for weeks spanning over a decade, the Coliseum would roar with the cheers of tens of thousands of fans and a new sold-out show every week. As cigarette smoke and bodies filled the building to the brim, the spectacle of bodies crashing against the ring mat became what could be described as an obsession.

“Memphians love wrestling,” Newt Metcalf said. “Memphis was one of the birthplaces of wrestling as we know it today … Every Monday night, there was live wrestling at the Mid-South Coliseum… It was packed… People up to the rafters watching live wrestling.”

One of the greatest feats of the era, however, was that wrestling was not confined to the arena. It bled into living rooms across the city every Saturday morning at 10:00 a.m. with a 90-minute run-time. Wrestling became the great equalizer, spanning generations, races and social classes — nearly everyone tuned in.

“Pretty much all of the community … either watched and liked [wrestling] … and admitted it or [they] watched and liked and didn’t really admit it,” Wiener said. “I mean, you know, people young and old, rich and poor, Black and white, all from Memphis, all liked wrestling.”

The magic of wrestling came from storytelling. Every match was a new chapter in an ongoing saga — good versus evil, friendships forged and broken and betrayals that could send the crowd into a frenzy. What was special about Memphis was the fans’ interaction with the story. What other cities and towns may not accept or believe would be taken with a passion that spread through the city.

“People were talking about it after the fact,” Metcalf said. “During the week, we would talk about what happened on the Saturday morning wrestling shows … There were storylines within the show … different people hated each other, and there were allegiances and broken allegiances.”

There were the clean-cut “baby faces” like “Handsome” Jimmy Valiant and masked men whose mystery would keep fans guessing. There were the pretty boys and the “jabronies,” a word whose origins likely lie in Memphis during this era, whose sole purpose was to be demolished by the main stars. There were female wrestlers, wrestlers that brought their pet pigs and sometimes even bears.

But one name towered above the rest. “The King” Lawler adapted to the Memphis environment — doing anything he could to win and to stay on top. Lawler began as a commercial artist working for Fargo, whom he looked to as an idol, and eventually made his debut as a wrestler.

“I wrestled by the rules and those people clapped for me but, you know, I lost every match I wrestled and I found out something about people in Memphis – they don’t like a loser,” Lawler said in an interview shown in the documentary “Memphis Heat: The True Story of Memphis Wrasslin’.” “When I lost those matches they stopped cheering for me, so I decided, boy, wrestling by the rules ain’t going to win any matches … I finally smartened up and I’ve been winning ever since.”

Early in his career, Lawler was not the “good guy,” but after gaining popularity and earning his crowning title, he truly became “The King.” Aside from wrestling, Lawler wrote the scripts for the Saturday morning programs, packing them with plot twists, infamous villains and enough suspense to enthrall viewers until the following showing.

“The biggest hero in Memphis was Jerry “The King” Lawler,” Metcalf said. “He was kind of a fan favorite and had a lot of tricks up his sleeve, like the Lawler BBQ, where he would throw fire in his opponent’s face. Villains like Jimmy Hart … he was a fast-talking, sort of despicable bad guy who would enrage the fans and do dirty tricks.”

Yet, before Memphis wrestling hit its true glory days, many wrestlers felt underpaid by the original owners of Championship Wrestling. That is until wrestler-turned-promoter Jerry Jarrett was swindled out of his share of the territories and broke off to form the Continental Wrestling Association. Not only did Jarrett bring many wrestlers with him, but he eventually brought nearly the entire production from Channel 13 to Channel 5. After winning the battle over the Memphis territory, the zenith of Memphis wrestling truly began. The show pulled a now near-impossible rate of 78% share of viewers, meaning that nearly 80% of those watching television at that time were tuned in to watch — all eyes were on Memphis.

“Memphis Wrestling was probably the biggest entertainment option available in the city,” Metcalf said. “There was a live TV show every Saturday morning on Channel 5. I think it was one of the highest-rated shows in the country.”

It was not just the ratings that made Memphis wrestling legend: the sheer insanity of the matches was unparalleled. Some rivalries became so heated that normal rules no longer applied and the crowd went wild every time — even when there was no crowd.

“It was such a huge rivalry [between Lawler and Terry Funk] that they decided they were going to have it at the Mid-South Coliseum without an audience,” Wiener said. “They had to have it in an empty Coliseum because it was just too dangerous.”

For those who had lived it, Memphis wrestling was more than just a show. Beneath the scripted chaos, there often was real pain, real danger and real stakes. Wrestlers had to protect themselves to stay relevant, to keep their medals — their honor. No matter how staged the matches were, real emotion came from them and the wrestlers pushed themselves to their limits, fighting and piledriving to oblivion.

“Kayfabe is a wrestling term,” Wiener said. “It’s like they create an entire narrative about the bad guys and good guys, and the commentators, the referees, everyone is in on it.”

But as the 1990s and 2000s rolled in, the world of wrestling began to shift — for what would be the last time in Memphis. As the industry grew more corporate, World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) absorbed many of Memphis’s greatest talents, taking them from the smoky, chaotic coliseum and placing them under the bright lights of a national stage.

“Wrestling [was] at its zenith in Memphis … then it moved more towards a corporate national production with WWE,” Metcalf said. “[Some of] the Memphis wrestling guys moved to the WWE for more of a national scale production.”

Years passed and time began to take its toll; wrestling began to lose its grip on Memphis. Television changed. Attention shifted. One by one, wrestling territories throughout the Mid-South fell as WWE took over small-town wrestling by promoting large-scale productions, and eventually, the Mid-South Coliseum became one of the only wrestling territories left standing amongst the ruins of an era slowly fading. However, Memphis laid the groundwork and the first platform for future stars such as The Rock, The Undertaker and Sting. But, as the WWE grew in popularity, the glamour wore off and Memphis was left behind.

“One of the reasons why we liked [wrestling] is because there wasn’t really that much else on … you didn’t have that many channels, so there was less distraction,” Wiener said. “There was something kind of charming about it before it got too big.”

After more than 20 years on WMC-TV5, Saturday Morning Wrestling was canceled in 2001, and what was possibly once the biggest show in the country became a memory in the minds of dozens of territories and thousands of fans. Now, the world of professional wrestling follows the whirl and action of the WWE. While a Friday Night Smackdown may occasionally make its rounds to the FedEx Forum across town, the Mid-South Coliseum stands empty — an untouched relic of an era unmatched by any other.

“It was definitely must-watch,” Wiener said. “The professional wrestling, the Championship wrestling show — I watched that every Saturday morning, all the way through college … I mean, it was pretty crazy … to the point it was a little bit dangerous.”