Lockdown. No entering or exiting homes, no going out to eat and no knowledge of what’s to come. And no, this isn’t about COVID.

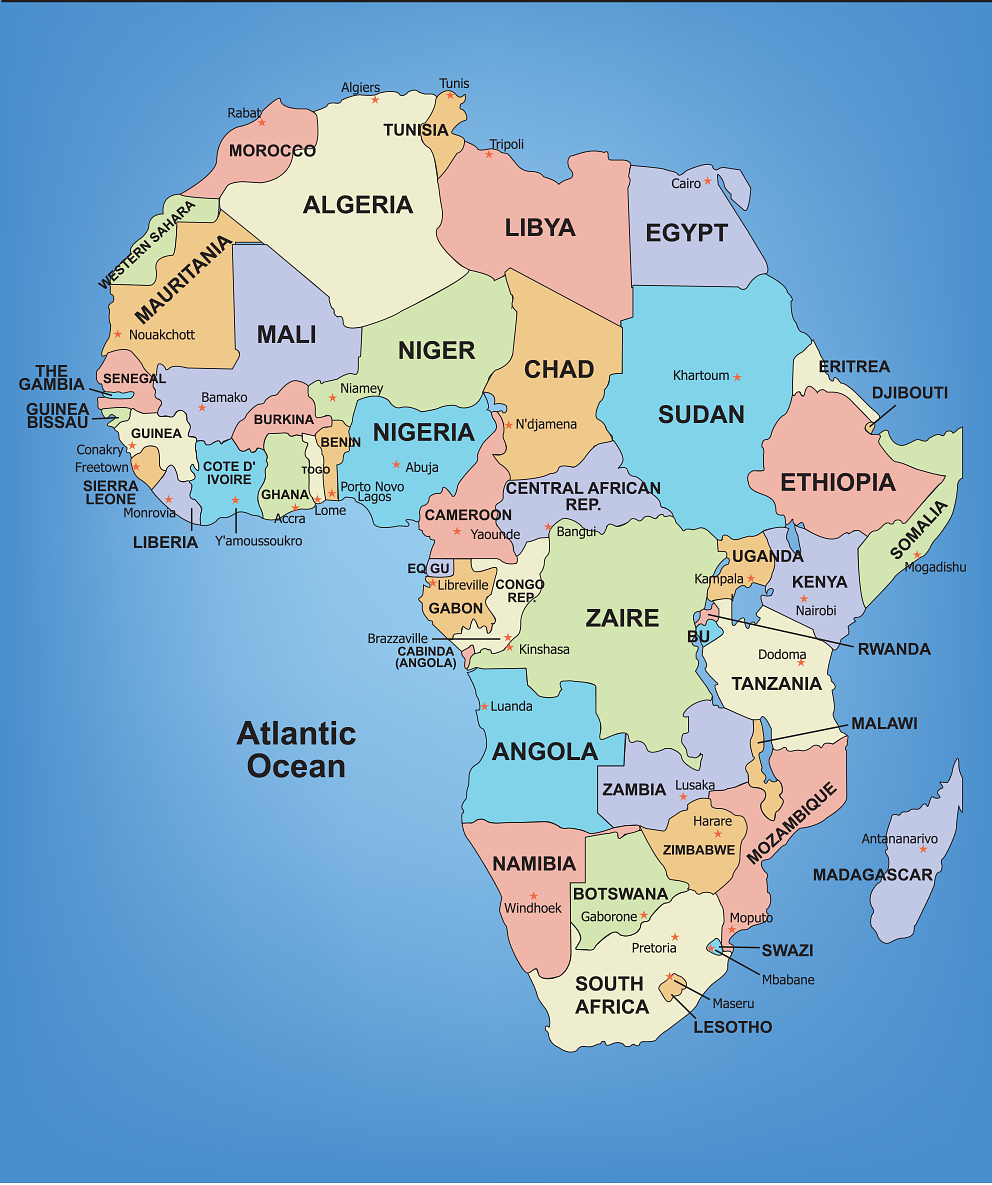

This uncertainty was prevalent in Bangladesh for many during the student-led protests which erupted last summer following a change to a quota system, which increased the number of jobs reserved for descendants of war veterans. People were left with no option but to remain in their homes due to a government-instituted lockdown and protect themselves from the surging violence, only leaving on certain days when they were allowed to. Both Dirayat Rahman (11) and Ashmita Karmaker (9) were in the capital, Dhaka, which was hit heaviest by violence when these protests were happening.

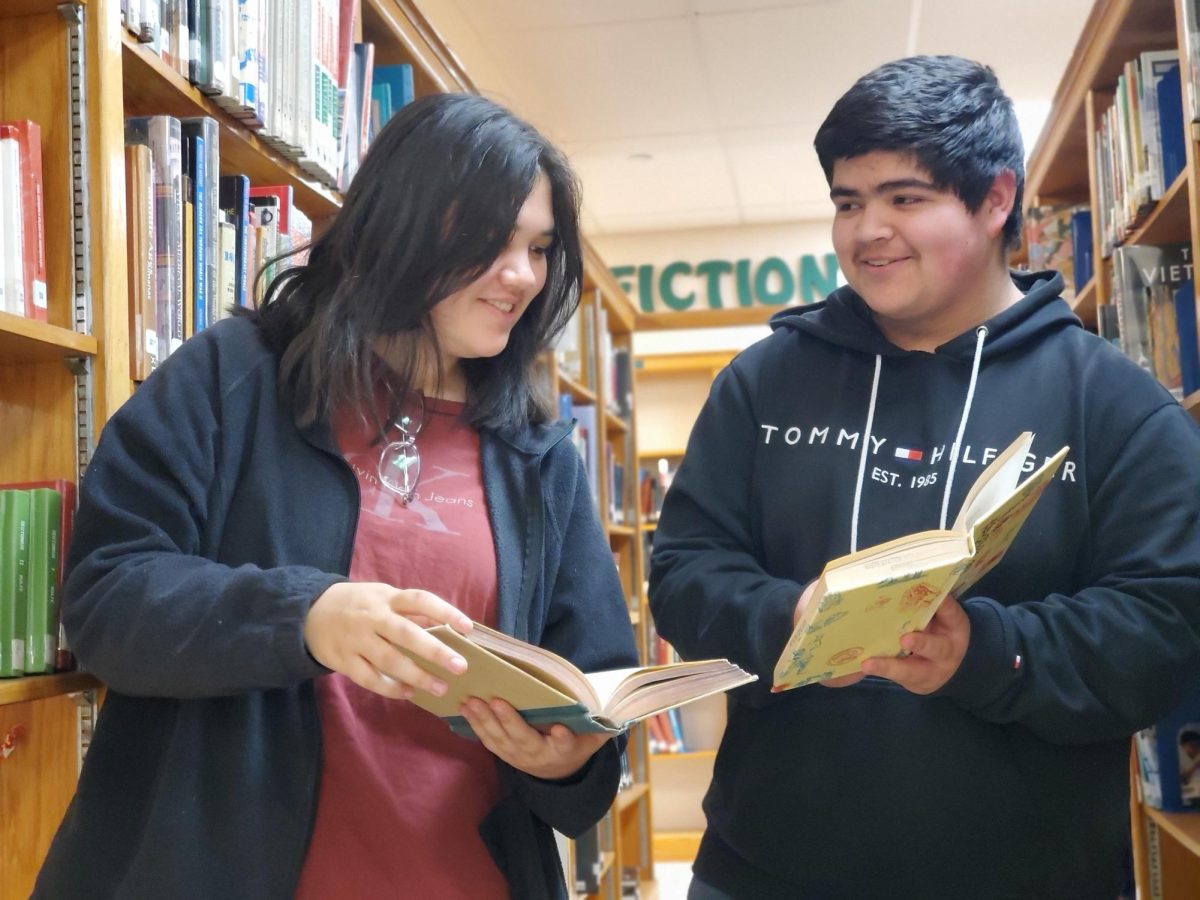

(ASHMITA KARMAKER//USED WITH PERMISSION)

“So do you remember when … [we] were in a lockdown in coronavirus?” Karmaker said. “It was something like that … because I stayed home most of the time — not most of the time, like all of the time — and I just saw people getting killed all of a sudden without any reason, so we were really scared.”

In contrast to the COVID-19 quarantine, there was no internet in Dhaka and a curfew was implemented, which made getting basic necessities difficult, let alone going out to restaurants and shops. The government would give notices to people telling them they could go out and buy food and other necessities.

“I had to stay home,” Rahman said. “I could not go out. It was five to six days before I came [Memphis] so I wanted to meet my friends. The roads were blocked … we had no internet for five days. Electricity wasn’t there for two days [and] two nights … people who did not have groceries, they could not buy groceries. And people were randomly being shot by the police and the armies of the country. And [the government] did not think it was important to … give any explanation.”

Many, like Rahman, speculate that the Bangladeshi government had intentionally cut off the internet; nevertheless, this lack of internet access made it more difficult to understand what was happening outside for the majority of people on lockdown. Even those who were aware of their surroundings could not reach other people to spread the information.

“They really don’t know how many people got killed, so they could easily give us false information through [the] news since we did not have anything to prove them wrong … social media is a powerful weapon for letting people know what’s going on, ” Rahman said. “Since everything was off, [few] people were aware of [what was] happening. And they could not let each other know what’s happening or connect.”

This conflict mainly occurred on account of the mistrust between Bangladeshis and their government, which culminated in the protests. Other students at White Station, such as Afifah Alma (11), shared similar sentiments.

“[The government] believed that communication was something that Bangladesh didn’t need with the rest of the world, because … propaganda would be spread because of that [communication],” Alma said. “Because they didn’t want more news to spread of the protest.”

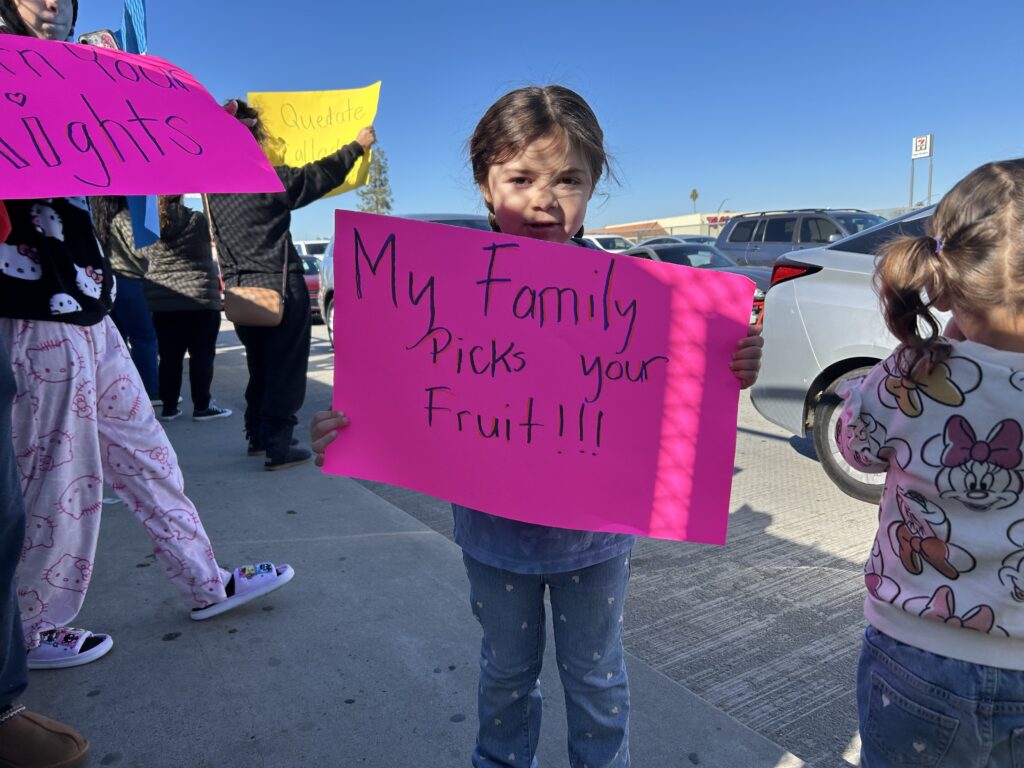

If buying enough to sustain themselves was difficult for the average family, businesses like restaurants struggled even more because the curfew kept food from being distributed overnight; restaurants could no longer function and serve customers, closing for days at a time. This struggle was Karmaker’s experience at a restaurant.

“My brother wanted to ask them again [for their food] because it … [had been] one hour already and when he was about to ask them … he heard that they were talking about getting food secretly, like … stealing it from some place because they had to run the business,” Karmaker said.

Even though people took shelter in their own homes, they took on the additional responsibility of protecting themselves because of how dangerous the situation was. They took on extra precautions to ensure their safety, like avoiding looking at the window and locking all doors and windows. Some families even had one person assigned to guard the outside of the home.

“[In] the middle of the night our family would sleep but then one [person]would stay outside to look for people if anyone came to … attack,” Karmaker said.

However, some of the fear that led to such precautions was not just from students protesting; it was also from the actions of the government. To many, the government intensified the violence through their violent crackdowns making people feel more vulnerable.

“[The police and army] were raiding the houses of [protesting] students,” Rahman said. “They … [were] trying to find out information and raiding their houses so that they can’t come out, and they even once declared [that] any student who is willing to come down on the road to protest or is wanting to protest … they will instantly shoot them.

Many attribute the cause of this lockdown and escalation in violence to employment issues. Changes to the already-existing public-sector jobs and university quotas benefitted only certain groups. This change meant that a third of the jobs would be reserved for descendants of veterans of Bangladesh’s War of Independence. Bangladesh was already facing very high unemployment rates with approximately 18 million youths unemployed with university graduates having a lower unemployment rate. According to the New York Times, these quotas collectively claimed over 56% of government jobs, which are some of the most stable in the country, offer many benefits and are very competitive with an acceptance rate of approximately 1.33%. Many students felt it was discriminatory because it did not recruit based on merit.

“So Bangladesh is a developing country … we don’t really have that many opportunities there so people really try to get into the public [universities] and jobs because that will secure them,” Rahman said. “A lot of people from villages go to public [universities] and change their life by getting an education and later on getting a job. When it was based on quota, the merit-based students were neglected … whereas someone who isn’t talented or isn’t smart, they’re getting into a really good subject or a job just because of [the] quota.”

But for many, they weren’t just fighting the quota, they were fighting what they believed to be injustice and infringement of their human rights through the prioritization of others on the basis of their lineage or ethnicity. To them, it was about the future, about the country that they wanted to live in and live for.

“Students did want to fight [the quota on descendants of war veterans],” Alma said. “They believed it wasn’t right [and] it got … to a point where it was such a big thing, where their lives had to be lost and things needed to be done, but it wasn’t done in the right way. Lives have to be lost for a new Bangladesh — for it to be completely different. People believe that … for a … new country, there have to be sacrifices … [the students’] deaths were like the first step for a new country.”

Even those who were not in Bangladesh were affected by the tension and harsh suppression of political opinions or dissent, like Alma and her family. Alma was born in Bangladesh and immigrated to the U.S. when she was six years old and has gone back to visit in 2017 and 2022. Her mother cares deeply about speaking up for what she believes is right because she was born right after Bangladesh’s War of Independence, a time where people began to reimagine the future of Bangladesh. She continuously posts about the situation on social media in an effort to not only increase awareness but also encourage those back home to speak up for what is right.

“[Alma’s mother’s] post got deleted … and my aunt actually got a call saying ‘your sister has done this … it would be in her best interest to just stop her account,’” Alma said. “But my mom, she likes to speak for what’s right … but after that happened, we did have to tell her to stop because … my mom’s not in Bangladesh, so it might not be her that’s suffering, but it will be the people that’s close to her, most of my family is there … however, she didn’t delete her Facebook.”

Despite all the lives lost, all the trauma and all that they have witnessed, many people still strive for a Bangladesh where everyone can coexist peacefully.

“I hope for a country where everyone, even if they’re not always happy … that everyone can at least be at peace with each other, be happy with each other, cry with each other, [be] frustrated with each other,” Alma said. “The thing is, everyone in Bangladesh, over 99%, we speak the same language. We all fought for our independence. So why can’t we share the same frustrations and anger and sadness together?”