Within the heart of the icy Svalbard mountains and under the glow of the northern lights, there lies a vault: a secure facility that safeguards over one million varieties of seeds from over 100 countries. But what is a seed vault? Who facilitated its foundations, and what else have they accomplished?

Throughout his career, Dr. Cary Fowler has engaged in a variety of roles both in and out of the government, quietly saving humanity one crop at a time. His work in agriculture, specifically his work in enhancing crop diversity, has left an undeniable mark on the world. And now, more than ever, Fowler’s past at White Station High School (WSHS) creates ripples of inspiration and innovation throughout the school.

“I’m happy with what people do with the idea [of the seed vault],” Fowler said. “If you really love diversity, in this case, crop diversity, which I do, then you also probably love people doing different things with it and there being diverse initiatives [to spread the importance of crop diversity and seed saving]. I’ve seen a lot of different organizations and different programs … [and] there’s a great diversity in all of those things.”

Fowler’s interest in agriculture began long before his time as a student at WSHS. His close connection to his grandmother and to the family farm helped root Fowler’s interests in cultivated land, not as a farmer, but as an agriculturalist.

“I grew up being very close to my grandmother who always wanted me to be a farmer,” Fowler said. “[Farming] just wasn’t something I could do … I spent a lot of time on the family farm just outside of Jackson, and I developed a real love for agriculture and love for farmers.”

Fowler attended WSHS from 1964 to 1967. Whether it was from the teachers, students or the clubs available at the school, he found himself introduced to the world in ways he never knew would impact his life today.

“White Station, I think, in those days, was a place where you could be exposed to a lot of different topics and disciplines,” Fowler said. “You could learn how to type and you could be a member of the debate team, and those two things were really important for me … [The debate team] taught me to think on my feet a little bit and not to be uncomfortable in public speaking, which is something I do almost every day now.”

The 1960s presented a new atmosphere for Fowler. The school was moving into desegregation, introducing Fowler to both civil and uncivil discourse; however, it was after attending both Rhodes College in Memphis, Tenn., and Simon Fraser University in Canada that Fowler fully connected his dedication to social justice with agriculture.

“[The idea of justice and equality] was very important to me,” Fowler said. “At the same time, back in my background was this love of my grandmother, her love of me and my love of the farm … I never saw those things connected. It was after college that I realized that [someone] could be involved in the issues of the day—involved in social justice matters—and then that could be applied to agriculture. And that was an epiphany and I never looked back.”

After working for a consortium of international agricultural research centers in Norway, Fowler realized the importance of protecting crop diversity. Although the seeds of important crops would be contained, their protection—especially in areas subject to violence and war—was limited. In some cases, seeds were lost to conflict.

“Much of this diversity, which was collected from farmers in developing countries, you can’t just go out and replace it,” Fowler said. “On an inflation-adjusted basis, our public expenditures and agricultural research and development are the same as they were 50 years ago. And yet, the challenges are much greater now. So we think we need a fairly dramatic increase in research and development. And if you look at the projections for food demand in 2050, the world needs to be producing 50 to 70% more food.”

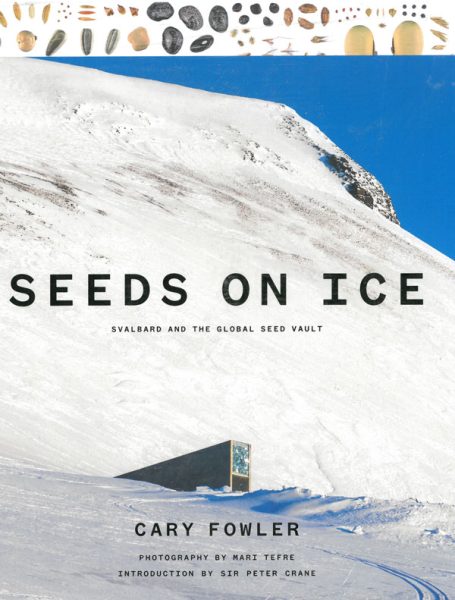

Fowler soon began planning the idea and construction of a global seed vault. It would soon become a sanctuary for seeds across the world to help protect them from global disasters.

“I had worked for a long time in and around the question of conserving crop diversity,” Fowler said. “Periodically, some of those collections [of seeds] would be lost … and I thought, ‘well, it’s only a matter of time before there’s a real disaster’.”

Ideas shifted from abandoned mine shafts to the final decision of tunneling into the mountains of the Svalbard archipelago. Fowler drafted a letter to be sent to the Foreign Ministry of Norway proposing an idea that would safeguard global crop supply. Upon return, Fowler was asked to form a committee that established the grounds for the creation of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

“Nobody had ever built anything like this,” Fowler said. “I realized that we needed a management plan that was really, really simple—almost foolproof—so we didn’t design the facility with a lot of complicated, fancy technology. We designed it so it was essentially run without human beings being involved.”

Fowler’s plan was accepted, and the seed vault was established in 2008. The facility is the only insurance policy for the world’s food supply, housing duplicates of 1,214,827 seed samples at a temperature of negative 18 degrees Celsius.

“The seed vault is like an insurance policy,” Fowler said. “And like any insurance policy, you never really want to collect on it. The seed vault has had many deposits from many different institutions around the world and most of them haven’t had to use the seed vault. That’s the good news, actually. I always thought that one of the best things that could ever be said about the seed vault, or me, would be that somehow I oversaw some kind of absolute useless boondoggle of a project near the North Pole that never had to be used. In a way, that would be fantastic.”

The response to Fowler’s project was so loud that it reached WSHS. Students used his work to establish their own seed library on campus, giving all students access to Tenn. native flowers, fruits, vegetables and herbs, allowing Fowler once again, to make his mark on the school. Although seed libraries are not made as an insurance policy like Fowler’s seed vault, they provide unique access to a community resource with a variety of plant species.

“I just never thought anybody would be very interested in [the seed vault],” Fowler said. “It always shocked me that there’s been so much media attention … I think [seed libraries] help to build public awareness about the importance of this resource. I’ve always thought that this is the most important natural resource on Earth. [Seeds are] the biological foundation of agriculture. I don’t think any natural resource is more important than that.”

However, Fowler’s work does not stop at the creation of the Global Seed Vault. He has served as Special Assistant to the Secretary General of the World Food Summit, and in 2015, Fowler was appointed to the Board for International Food and Agricultural Development by President Obama. It was not until 2022 that Fowler officially joined the United States Department of State as the Special Envoy for Global Food Security.

“Essentially, I’ve spent my whole life trying to figure out what to do next or what best to do next that was involved in that general field [of agriculture], and I’ve been pretty lucky about being able to do that,” Fowler said.

Recently, Fowler has been working to promote The Vision for Adapted Crops and Soils (VACS), a program that is co-sponsored by the African Union and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN promoting the plant breeding of indigenous crops in Africa.

“In Africa, there are more than 300 indigenous crops that have never had the kind of attention or investment that our crops in North America have had,” Fowler said. “These crops have never really realized their potential and that’s particularly sad because, not just with hunger in Africa, but [also] hunger and malnutrition [in general]. These crops can be very nutrient-rich and therefore have a lot of potential for helping with things like childhood stunting.”

Fowler has helped prioritize a list of about 60 crops that are believed to have the most potential to adapt and provide the most benefit as a food supply. Fowler believes that the message of his projects is that the adaptation of these plants to any environment is what allows for crop diversity to increase food growth.

“I have been growing one of those crops [from one of my programs] for some years,” Fowler said. “I have been growing that plant, the 48 different varieties … to try to make selections to essentially adapt that crop to my farm in N.Y. … [The plant is] really adapted to very dry, hot conditions, but ok, there’s diversity and this is the whole message: plants evolve, they adapt.”

Throughout Fowler’s life, he has received support from a multitude of individuals who have allowed him to pursue his mission as someone who stands for the betterment of food production through increasing and adapting plant diversity.

“For me, there have been a lot of people that have opened doors for me and made opportunities for me,” Fowler said. “And when I look back on it I wonder why they did that, what they saw, why they would ever give me that chance … There were teachers from high school all the way through graduate school that [encouraged me.] I can’t really imagine having done anything worthwhile that I have done in my life without that type of support.”

Looking back on his time at White Station, Fowler believes that he should have studied more foreign languages. Although he could not have known where his path would take him, he views self-expression as an essential part of any career.

“Regardless of career or profession, the ability to speak and write properly is essential to success,” Fowler said. “My father, who was a judge in Memphis for 22 years, said that he thought being an English major in college was the best preparation for being a lawyer. In my experience, the ability to express oneself is critical as well in all the scientific professions.”

Fowler encourages students to be open, to take chances and to take advantage of the diversity of White Station. Although no student is fully aware of what their future holds, just as Fowler was unaware of what his job would entail, anticipating change and adapting to any problem shines a light not only on an individual’s future but that of a global and interconnected community.

“Once you get out of school, life doesn’t separate itself into social studies and biology and math and things like this,” Fowler said. “It’s all combined and you have to think in a cross-disciplinary way and you have to connect the dots. I can’t think of a single major or world problem today that can either be understood or solved within the confines of a single discipline. And so my advice is to kind of be open and realize that whether you can connect the dots now is maybe not the measure of the value of studying something. We’ll connect the dots later.”