Tradition and dedication collide for arangetram and rangapravesam

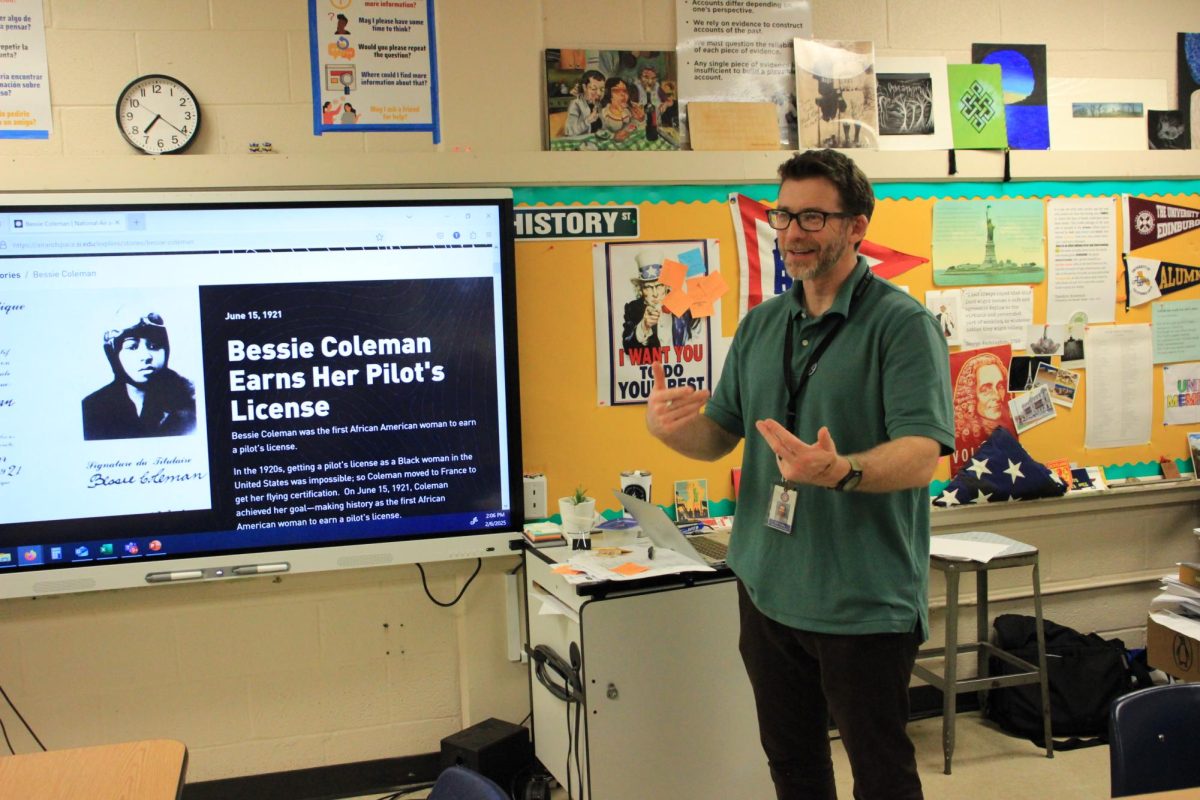

SURESH MARADA//USED WITH PERMISSION

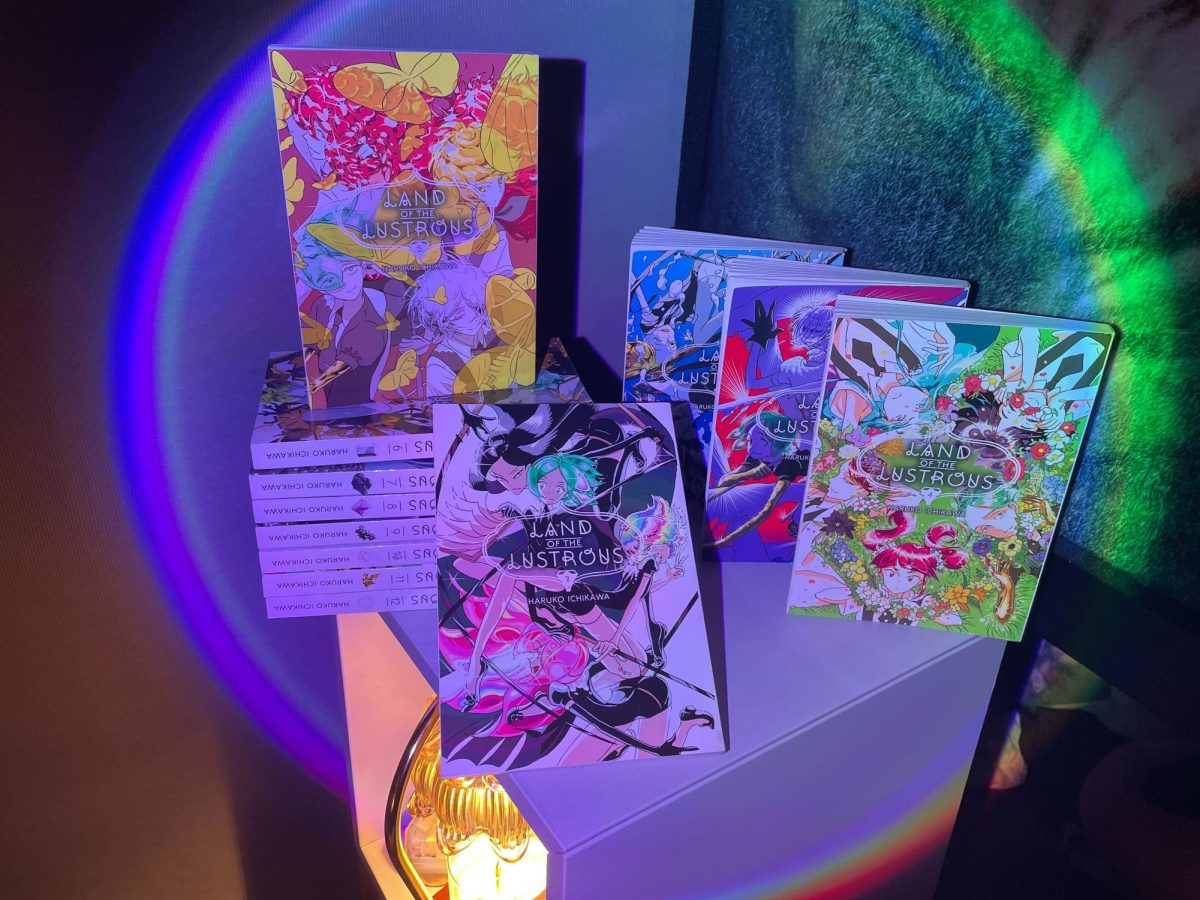

Spoorthi Marada (12) dons a blue dance costume for a kuchipudi recital on Feb. 26, 2023. While Marada has performed in recitals like this multiple times already, the rangapravesam will still serve as a monumental event.

The thump of bare heels on the floor and the clink of delicate bangles accessorize the sound of rich, rhythmic music. After years of preparation, arangetram and rangapravesam serve as precious opportunities for Indian dancers to showcase the skills gained from extensive hours of disciplined practice.

Arangetram and rangapravesam are both terms that denote a special performance done after mass amounts of preparation. The terms indicate different styles of dance, with an arangetram being a showcase for bharatanatyam and a rangapravesam being a showcase for kuchipudi. Though the style of dance for each differs, the meaning behind them is the same..

“It’s known as a graduation,” Arya Rajesh (12) said. “If you look it up it’s like ‘the performers’ first time on stage,’ but like that’s not true for us, because we’ve performed in events and stuff before. But it’s like [the] first time that a dancer gets to show off what they’ve learned for so long.”

Rajesh and Shivani Menon (11) have been trained in bharatanatyam by Gayatri Seshadri, an instructor currently based in Atlanta. This physical distance led to a majority of their training being held over Zoom, with occasional in-person meetings to make corrections. Meanwhile, Spoorthi Marada (12) is training in kuchipudi, another style of traditional dance, with Aparna Vhatla, a well-known instructor in the Memphis area.

“Kuchipudi is more about … not expression, but my teacher always describes it as more feminine,” Marada said. “It’s more flowy and about storytelling; there’s a lot of parts in some dances where it’s just music, and it’s not really footwork, it’s more about your face.”

Rajesh, Menon and Marada have all been training in their respective styles of dance since around the age of 4 or 5. As practices went from group to individual and once a week to almost every day, the preparation for an arangetram or rangapravesam is expensive: both in terms of cost and time. Performances like these can end up costing around $15,000, and most dancers, including Rajesh, Menon and Marada source things like jewelry and handmade sarees directly from India.

“It’s definitely a lot more expensive if you try to get anything here, [and] it would be very limited … because a majority of people doing this across the country are going to be going back to India for all this stuff,” Marada said. “In a way, you can put more trust in the person too because they do it so much, it’s their livelihood.”

The final performances themselves tend to last around two to three hours, with about nine different dances and abreak in the middle for the dancer to change costumes. In the Indian community, these performances are affectionately referred to as “weddings without the groom,” poking fun at the grand scale of each. Due to the extensive planning necessary to pull off an event at this scale, the dancers cite their parents as an indispensable support system for the process.

“It was my mom’s dream because she didn’t get to dance or do anything like this, so she wanted me to do it,” Menon said. “They put their best efforts [in to] making sure everything went well. They called people, organized everything; they did such an amazing job handling everything. My dad woke up at like 2 a.m. afterwards to drop people off [at the airport], and we couldn’t have done everything without my parents. They were 75 percent of everything.”

Training for an arangetram or rangapravesam requires building stamina both physically and mentally. For Menon and Rajesh who both struggle with asthma, physical endurance for the multi-hour performance was a primary concern. Marada, on the other hand, faced a mental block when developing the expressive elements of her dance.

“Physically, it’s not that straining because I’m used to it, like my endurance is fine,” Marada said. “In one dance, I’m just on my knees for like 2 minutes, which … is not very physically taxing or anything but … making sure that I do justice to the dance, and what it’s supposed to be, and not letting the fact that I feel kind of dumb or any negative thoughts about how I’m perceived or anything get in the way.”

Beyond familial and personal importance, the dance is also an homage to Hinduism with a variety of figures and stories associated with it. Some individual dances will focus on representing a specific god, or tell a fable that displays honorable characteristics of a god or goddess. For Rajesh specifically, learning bharatanatyam and preparing for her arangetram significantly enhanced her connection to Hinduism and its beliefs.

“I will say that this helped me understand and brought me closer to my religion, because I’m able to understand stories and understand the gods and goddesses and their roles better,” Rajesh said. “Before, when I did less of the storytelling, I had a general idea, but now I feel more connected … a lot of the time for the stories you have to be connected … you can’t really express your devotion to a god without knowing about them.”

Between the frequent practices, excess strength training and tedious memorization, dedicating years of a lifetime to dance can seem daunting. It often takes dancers time to make the choice whether they will pursue an arangetram or rangapravesam. For Menon, the final feeling of triumph when the music cuts and the audience erupts makes each bead of sweat worth it.

“When I say ‘it’s all worth it,’ I’m definitely going towards the feeling after the performance,” Menon said. “Finally finishing those three hours and looking at all of your family members … astonished and proud of you, it’s such an accomplishment. You’re gonna get so many emotions, like ‘I’m finally done,’ and all the time intensively training and finally seeing everyone be proud of you is all worth it.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of White Station High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.