The ripple of Tyre Nichols

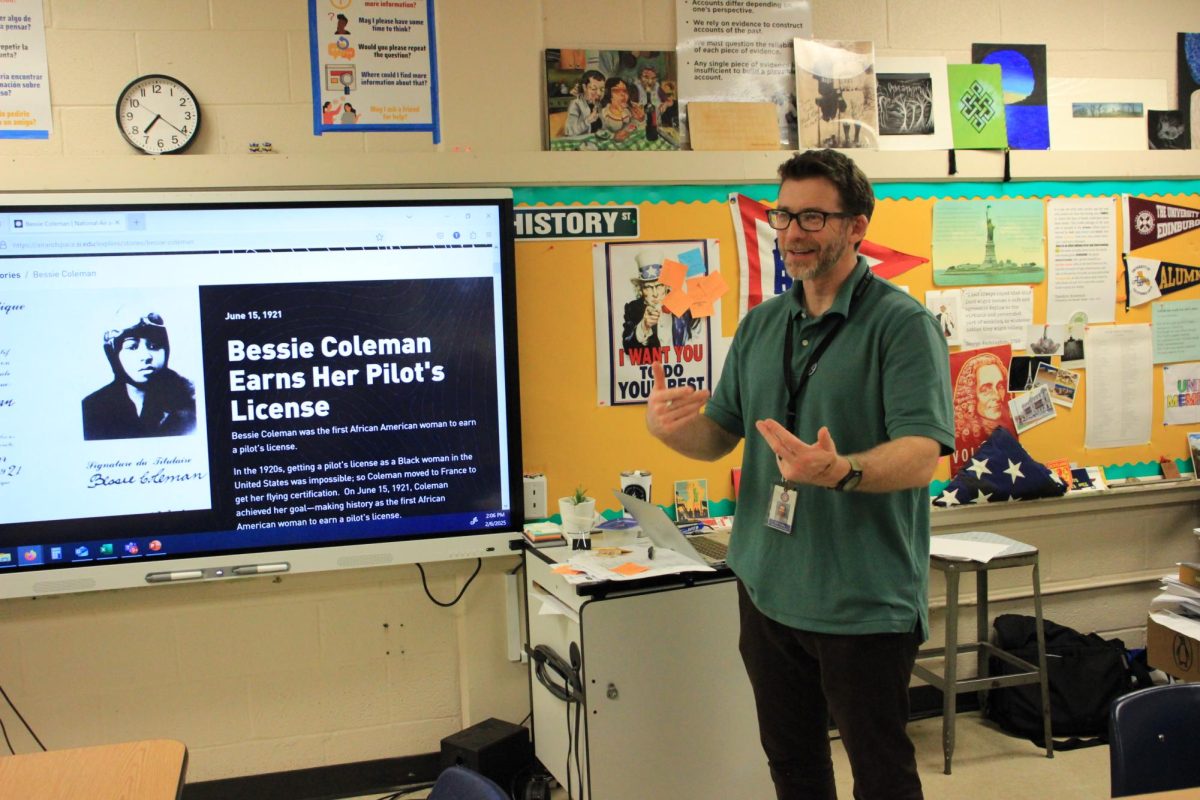

SAM HORROCKS//USED WITH PERMISSION

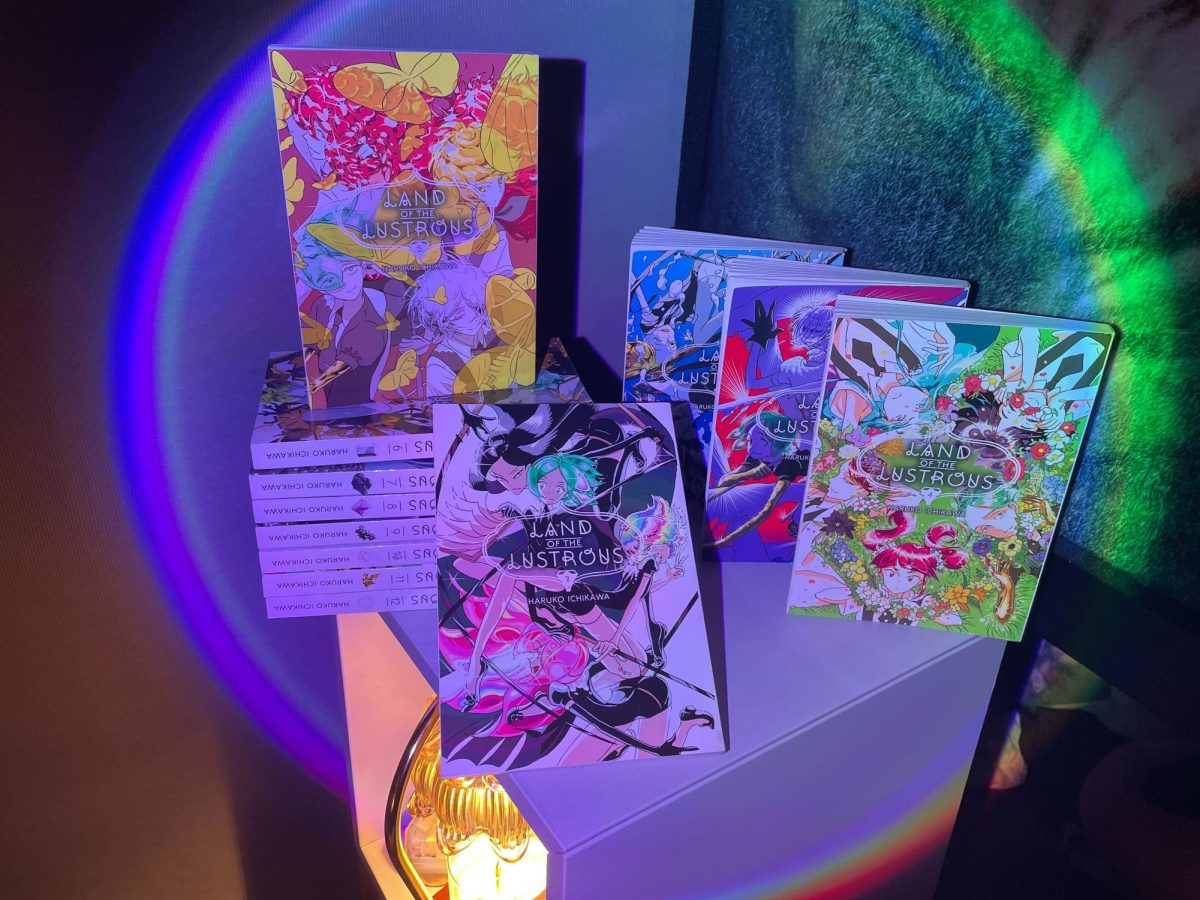

Skateboarders gather at the MLK Memorial in Memphis. They skated around the plaza in remembrance of Tyre Nichols’s long time love for the sport.

Tyre Nichols was a 29-year-old black man living in Memphis, where he brought along his love of skateboarding and photography from California. Nichols was harassed by a group of Memphis Police Department (MPD) officers on Jan. 7 and subsequently died in a Saint Francis Hospital on Jan 10. Nichols was first pulled over for reckless driving and several officers began to beat him despite his full cooperation. He ran from them out of fear until he was caught in his neighborhood, where they jumped him until he was unconscious. When medical service was called, two EMTs neglected Nichols for twenty minutes before even touching him. In the week following the incident, seven MPD officers and three EMTs were fired. Five of the officers were charged with second degree murder and a multitude of other charges.

“Any time something like that happens, it affects the whole community,” Officer Franklin Wade, a White Station security officer, said. “It sets everything on high. And that leads off to family, homes and schools.”

On Jan. 27, the city released body cam and street pole camera footage of the encounter. This gruesome video also sparked protests across Memphis, resembling the impactful Black Lives Matter riots in 2020. From Jan. 27-28, Memphis Shelby County Schools canceled all after-school activities for two days in reaction.

“You don’t want kids on the street, buses running during all of that,” Wade said. “We were trying to keep kids away from any place that may have been volatile. I’m here to protect you, to keep you all safe and to make sure you get back home the same way you came … at the same time we have to protect the teachers too and the building, all of that.”

It was a community wide shock. People either protected their family in recluse or got active. On Jan. 26, a vigil for Nichols was held at Tobey Skatepark. On Jan. 30, people organized another vigil at Shelby Farms. Memphis was not alone. Big cities across the country held protests the day of the video’s release and the following weekend.

“It’s significant because he was one of us,” Courtlan Black, a skater and rapper under the name Geepmane at Central High School, said. “It sounds cliche, but the skate community is kind of like this big family of sorts … of delinquents, doctors, lawyers and whoever. Everybody knows everybody. [The skate community] has been the most connected it probably has ever been, honestly.”

Of course, this event has caused another massive wave of mistrust between the public and police. MPD Police Chief CJ Davis made a public statement on Jan. 26, and Steve Mulroy, Shelby County District Attorney General, held a press conference on Jan. 27. Both of these talks aimed to assure the community justice is being served and changes are being made within the MPD.

“I truly believe there are more good cops,” Black said. “But unfortunately, when cops do bad things, it makes the entire organization and police force look terrible … I don’t feel like there’s any real accountability in the police force. It’s making people lose hope, a lot of hope.”

This incident could have happened to anyone. It was the officer’s will that brought the situation to an extreme, which makes it hard for a community like Memphis to trust police. It can be hard to escape this circle of distrust, but big change starts with little decisions. It can start with placing a little trust in the people protecting the school.

“It saddens me to see the good that we do out in the community get tarnished by somebody that’s so ignorant and did something so heinous as to abuse their authority like that,” Officer Robert Stewart, a White Station security officer, said. “It’s not what most of us joined law enforcement to do. It’s not what we’re trained to do.”

Officer Stewart and Wade have both been in the police force for around twenty years. They have been working with MSCS for six years, with a range of elementary, middle and high school experience. They are seasoned veterans used to working with vulnerable people and keeping that trust for a long time.

“I enjoy working in elementary schools because when they’re little you can help them understand that we are here to help you, not to do you harm,” Wade said. “Don’t tell a child to fear us. Because when they fear us, who are they going to go to in a troubled time … you have to be able to have a good relationship with the police because those are the people you’re going to call in a time of need. Don’t ever feel like you can’t approach a police officer.”

These people are not here to hurt or discriminate against students. They have a family of their own. It is best to think past the badge and past the stereotypes. But, of course, every civilian is entitled to their opinions and bias in some cases. Altercations can be delicate, which is why it is important to strip away the fear from this prey-predator relationship that seems to plague our community.

“Us in the school, we have the same badge, the same gun, the same patches as an MPD officer has, so it makes them look at us,” Stewart said. “Sometimes they already have a bad opinion of us due to a situation like [the Tyre Nichols incident] before they even get to know us. A lot of students walk past us and don’t ever get to know us. So, all they have is those opinions on authority figures … there is good being done out here in law enforcement.”

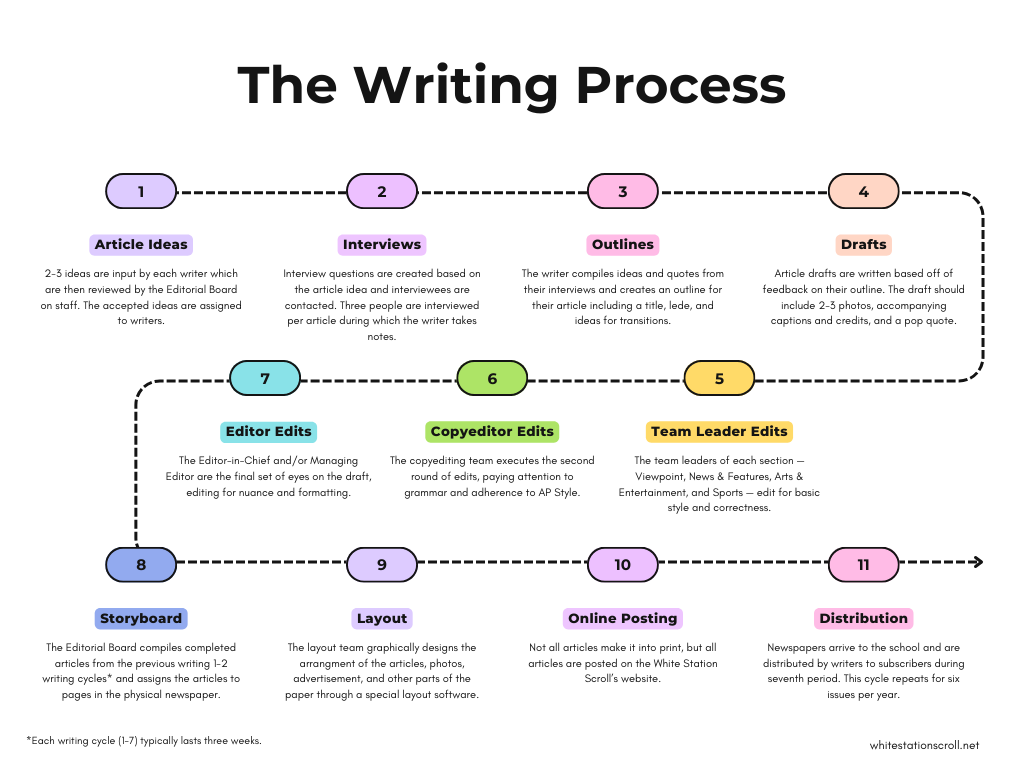

Your donation will support the student journalists of White Station High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.