Kwanzaa: a week of unity and culture

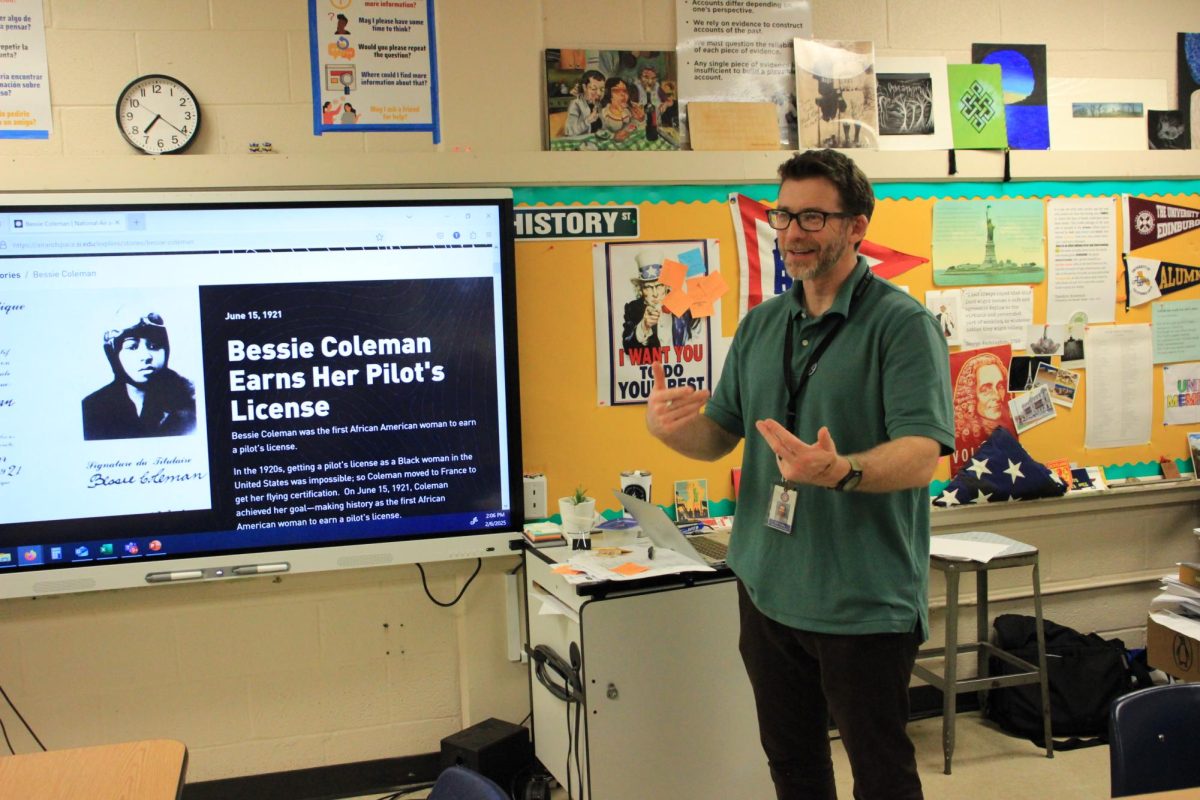

The kinara, which holds seven candles, is lit by celebrants of Kwanzaa. The candles are a physical representation of the seven principles of Kwanzaa or the Nguzo Saba.

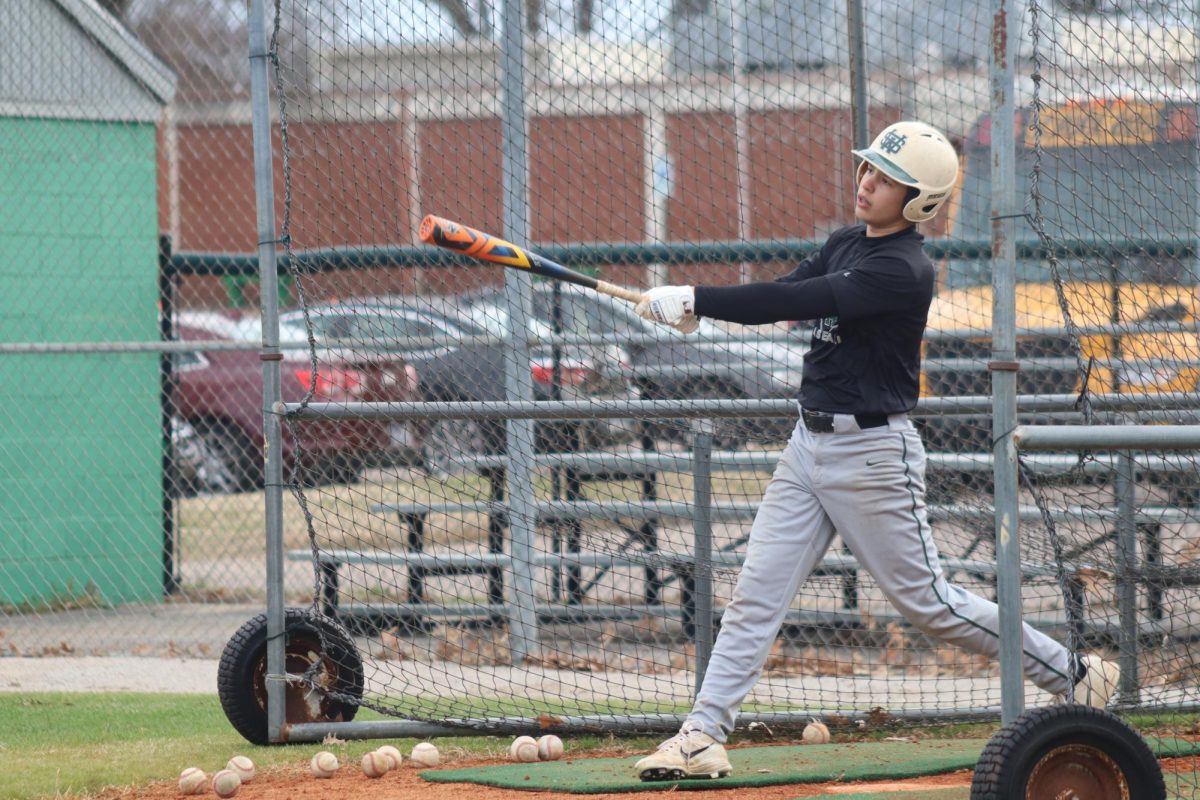

It’s the final day. Foods ranging from fufu and Nigerian puff puffs to mac and cheese and okra are spread across the table as Jaden Clark (11) enjoys karamu, the celebratory feast of the holiday known as Kwanzaa, with family and friends.

On Dec. 26, when many have finished swapping gifts and feasting, a celebration is just beginning for the small percentage of Americans that observe the week-long holiday. Created in 1966 in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement by a professor of Black Studies, Maulana Karenga, Kwanzaa is a celebration of African culture.

Although it is not a religious holiday, Kwanzaa can be observed in a multitude of ways ranging from singing to dancing to reciting poetry. For Clark, he first began celebrating five years ago with his family.

“I was at my cousin’s house … and my mom called me, and she said, ‘I’m about to pick you up, so you can celebrate Kwanzaa with us,’” Clark said. “… I was really blindsided, so at first I was like ‘No,’ … but I was forced to, but I’m glad I was.”

A brand new experience at the time has now become tradition for Clark as he participates in all seven days of Kwanzaa, which each represent a different value. The days are Umoja (unity), Kujichagulia (self-determination), Ujima (collective work and responsibility), Ujamaa (cooperative economics), Nia (purpose), Kuumba (creativity) and Imani (faith).

“For those who don’t celebrate, I wish they knew how enlightening it is because we all know the values. … but when you start to celebrate, or at least for me when I started to celebrate, I truly gained a deeper understanding of all of the values … and you know, it changed my life,” Clark said.

For each day of Kwanzaa, a candle can be lit on the traditional candle holder, the kinara, to symbolize that day’s core value. Other common occurrences throughout the holiday are discussions of the values and the overall theme of unity — as one of the holiday’s original reasons for creation was to bring African-American people together.

“At the end of each day, you would grab hands and chant ‘harambee’ which … means ‘all pull together,’ … and it would be a sharing of our energy as a collective and just appreciating each other,” Clark said.

Despite Kwanzaa holding special meaning to some Americans, many are unaware of the holiday. Some celebrants like English teacher Sharmika Harris, who started participating three years ago, have their own beliefs about why the holiday is so hidden from American society.

“I think Christmas overshadows it … Santa Claus and gifts [are] kind of hard to beat,” Harris said. “It’s also new for a lot of people … [Americans not knowing about Kwanzaa] just shows where we are as a country and what we pay attention to. I also think that the principles of Kwanzaa are things that we should be doing anyway … when you talk about faith and purpose and creativity, those are things that we’re working on daily.”

Although the holiday was created for African-Americans to celebrate family, community and African culture, Clark believes that more Americans that do not celebrate should be aware of the holiday. He is not surprised by the lack of knowledge surrounding the holiday and feels disappointment.

“When it comes around like late December, people will say ‘happy holidays’ because most people either think you’re celebrating Christmas or Hanukkah,” Clark said. “But nobody really knows about Kwanzaa, which is understandable because it’s really [a part of] black culture, and there are a lot of people out there who do not appreciate black culture or who don’t want to learn about it. … You don’t have to go into full depth of what Kwanzaa is, but just acknowledge it. Maybe even appreciate it because it’s good to know other people’s cultures.”

A common misconception is that one cannot celebrate Kwanzaa and Christmas, but as Kwanzaa is a cultural holiday, it is normal to observe both. For those looking to dive deeper into their own culture or learn about a new culture, there are ways to get involved locally through educational organizations and community events.

“It’s not a negative to celebrate it because when you look at the principles … it’s what we already need to be working towards,” Harris said. “Especially for those who are trying to get more connected to their cultural background, where they’re really from and what their ancestors believed and valued. I think that’s a good start.”

Clark, who was reluctant at first to celebrate, has now welcomed Kwanzaa as a yearly tradition. On his favorite day, the final day, Imani, he partakes in Karamu and joins in meaningful conversations that are one of many reasons why Kwanzaa is so special to him.

“I don’t want to say it means everything to me — that’s so cliché — but it really does though, because it’s really [about] families coming together, communities coming together, celebrating this one thing,” Clark said. “The love, the happiness, all of the energy that comes from it and that’s created — it’s just amazing really.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of White Station High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.