Memphis stands up to white supremacy

Nathan Bedford Forrest statue in the Health and Sciences Park.

In early August 2017, a group of white supremacists met in Charlottesville, Va. to protest the removal of the statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee. The protest in Charlottesville captured the nation’s attention and sparked attempts to take down other offensive monuments in hundreds of cities across America, including Memphis, Tenn.

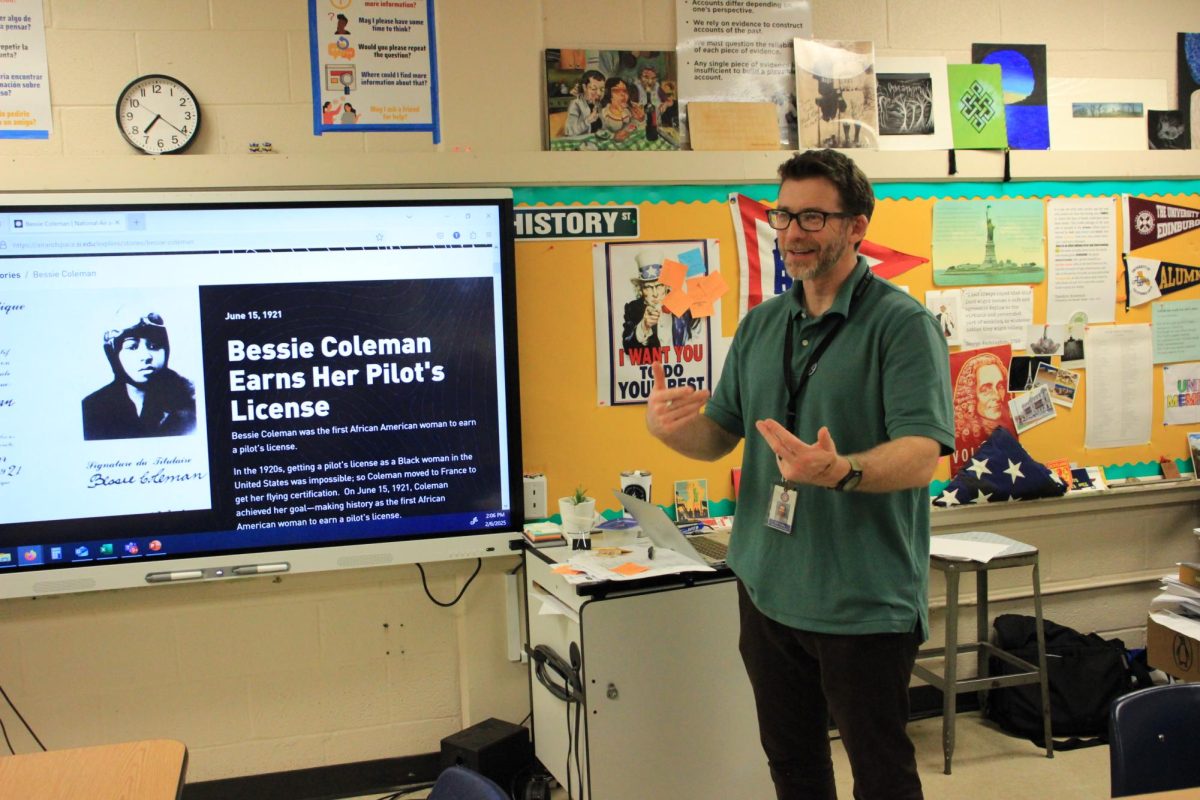

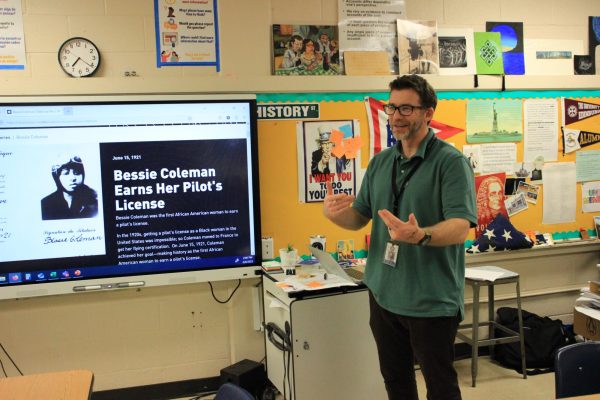

On Aug. 19, Memphians rallied in front of the Nathan Bedford Forrest Statue in the Health and Sciences Park as part of Memphis’ “Take ‘em down 901” movement. They were joined by White Station government teacher Curtis Rakestraw, as well as economics and personal finance teacher Bill Stegall.

Forrest was a general in the Confederate army, infamous for his involvement at Fort Pillow, where his troops massacred a troop of black soldiers. He was also one of the key founders of the Klu Klux Klan. To a majority of Memphis residents, his statue represents decades of racial oppression.

“I think it’s important that our local leaders understand, and I think they do, how much people care about removing those statues and that imagery from our public spaces,” Rakestraw said. “It’s been beyond time for those statues to come down.”

The protest began peacefully. Hundreds of Memphians assembled, holding up signs and criticizing local leaders for not doing enough to take the Forrest statue down. The police were acting as observers until some protesters began to climb the statue, while others began wrapping a banner around it that read “end racism.”

“When we did that and when we climbed on the statue, about 30 police officers charged the statue,” Stegall said. “They were pushing and kicking and shoving us to take that sign down.”

Instead of arresting people who touched the statue, the protest would have been more peaceful if the police had simply waited until the protesters left to remove the sign.

“Even though I think the police were poorly lead in that moment, one of the good things that happened was a lot of the protesters started having heat exhaustion and the police were very receptive and helpful,” Stegall said.

Although the Tennessee Historical Commission is currently protecting Memphis’ Confederate statues, at meeting on Sept. 5, Memphis city council members discussed defying the commission and taking them down.

Students can be a part of the fight against white supremacy. Not necessarily by protesting, but with an informed opinion.

“I don’t think it’s important for students to protest at all, but I do think it’s important for students to know what’s happening and be a part of the argument,” Stegall said.

The final verdict for the existence of the statue will be released Oct. 3.

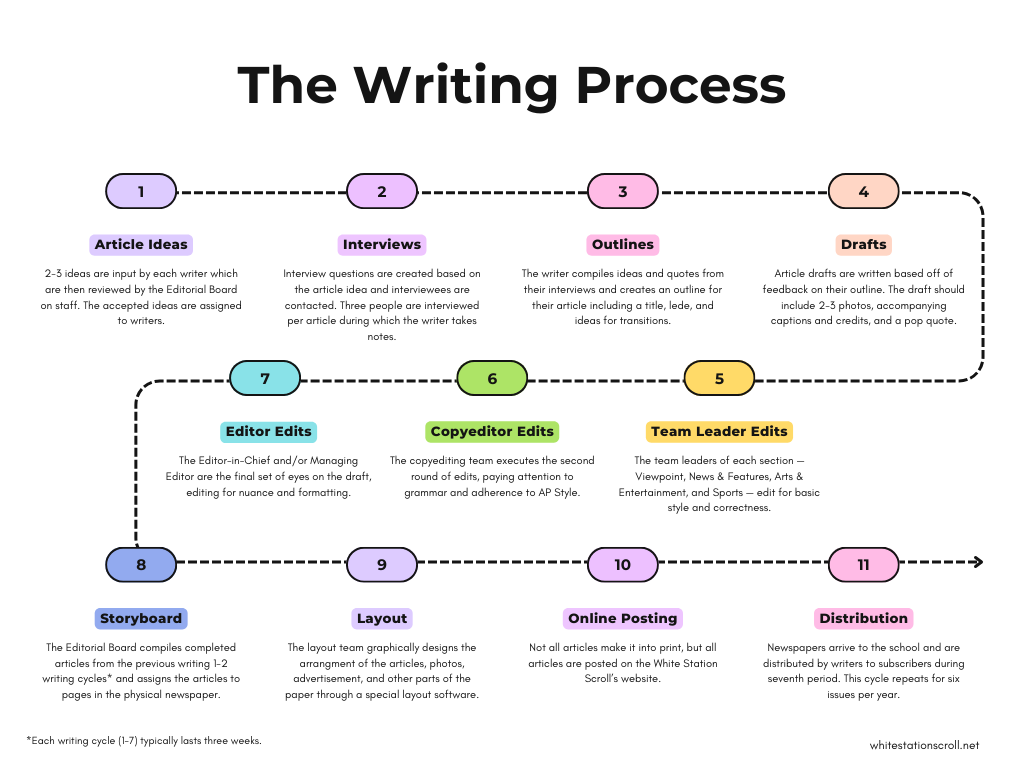

Your donation will support the student journalists of White Station High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.