The trials of a lifetime

“I remember thinking to myself, ‘This is my school. ‘”

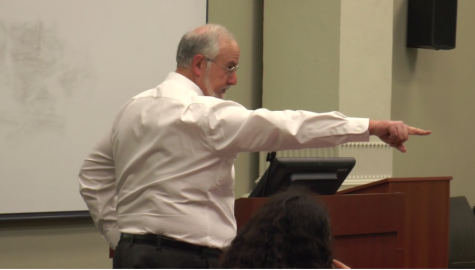

Eugene “Buddy” Bernstein took me through a time machine. I no longer sat in the home of my coach and teacher for the past four years; I was

in the halls of White Station during a time he deems “the Tough Period.”

“I would walk into the school in the afternoon and feel uncomfortable. Kids hung out in front of the school and acted scary,” Bernstein said. “I think it had to do with the music and the culture of the time, but it passed.”

For over four decades, Bernstein has witnessed the highs and the lows of White Station. He himself graduated from the school in 1971 and later watched all of his five children do the same. He remained a constant as the school saw changing diversity, varying academic standards and a handful of new principals.

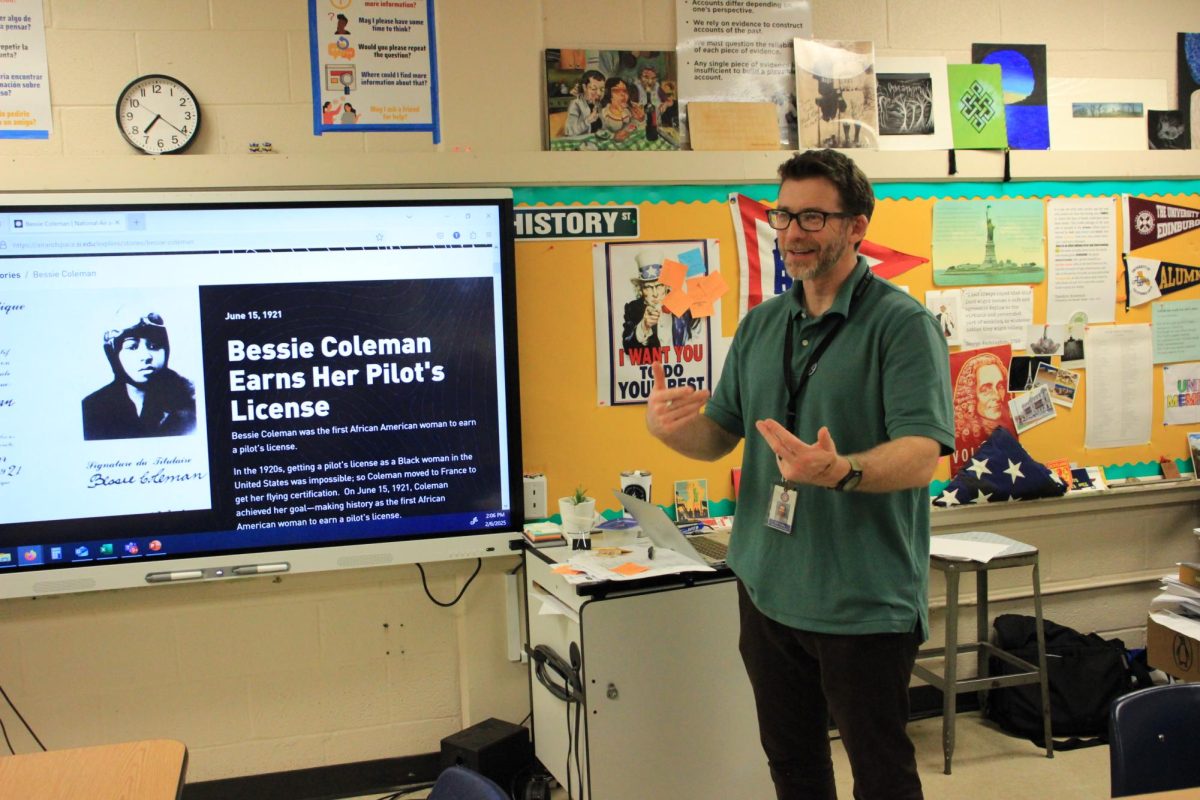

But it was in 1980 that Bernstein began what would be his greatest contribution to White Station: the mock trial program.

“Mock trial is an academic activity. It is a competition where students play the part of lawyers and witnesses based on a set of facts given to us, yet nothing is scripted,” Bernstein said. “Lawyers must learn the rules of law and structure evidentiary arguments.”

However, when the team was founded, Bernstein himself wasn’t even a lawyer; he was a second year law student at the University of Memphis. A classmate had heard news of the mock trial team started at Georgetown University a few years prior and wanted to bring

the program to Memphis.

“He came up to me one day and said, ‘Do you know what mock trial is?’ and I responded no,” Bernstein said. “Then he said, ‘Well, you’re going to coach high school mock trial.'”

Since then, Bernstein has taught some 600 students during his 35 years as head coach. And like White Station itself, the mock trial

program has also seen its changes.

“It has ebbed and flowed. We started out as a really powerful team, and over time the team became less powerful,” Bernstein said. “Most years we’ve had extremely strong students. It’s just a matter of effective coaching…There’s probably a correlation between the ages of my children and the success of the team.”

In the beginning, the same few public schools dominated competitions. Over time, however, the program has grown to include schools, both public and private, from across the city. This past year, a total of 24 teams competed in Memphis’s district competition alone.

And of course, Bernstein has also experienced growth as a coach and teacher.

“Frankly, I think there have been no big challenges [with the team]. There have been lots of little ones,” he said. “I think over the years, my

own ignorance and ineptitude as a teacher has been the biggest challenge—learning to manage my expectations, figuring out what was important.”

To become a more effective coach, Bernstein didn’t have to look far. He found inspiration in his White Station teachers, a few whom Bernstein remained friends with for years after graduation because of mock trial.

“I’ve tried to emulate teachers who sought and found the spark in students or who provide the spark in students,” he said. “I always wanted to be the teacher my students looked at and said, ‘He’s very hardworking, and he’s working for me.’ That’s what I’m after.”

Taking a few teaching courses also didn’t hurt. Years ago, while enrolled at the University of Memphis’s Masters in Teaching program, Bernstein took a course on adolescent psychology that gave him new insight. The class focused largely on cognitive ability and children’s brain development.

“I came to realize what we as humans can and cannot do before we are 25 years old,” he said. “The trick was to find ways to enable students to do

something beyond your own cognitive development… It’s about getting each of you to think in particular ways, getting you to engage in analysis with minimal guidance.”

Yet instructing students on how to perform sharply and ultimately win was not Bernstein’s biggest goal. Rather, he hoped to lead by example and instill certain values in his students.

“I tried very, very hard to be cognizant,” Bernstein said. “[I’ve tried] to demonstrate the values that I wanted all of you to emulate.”

In an activity like mock trial, where students are bound to a strict set of case materials and must prepare intensely for competition, the two most

important of these principles were honesty and dedication.

“I think there’s hardly been a person on the team within the last decade that hasn’t learned [the importance of these values] if they didn’t already know it coming in,” Bernstein said.

Because of these far-reaching goals, Bernstein has made incredible friendships with students, parents and competitors alike. In some way or another, he has impacted the lives of hundreds, including myself.

“Almost all of the students whom I have coached would have been successful, productive members of society without my help, so I have provided an enhancement for [those students],” he said. “But there are a few whose lives I have significantly changed for the better. Just a few.”

Bernstein remembers one student in particular who experienced such an effect.

“To say she was afraid of her own shadow was the understatement of the decade. Her hands shook, she hid in the back of the room even after

the first year,” he said. “But, she didn’t quit.”

Bernstein later learned that the student’s parents had both been living with cancer for much of her life. Her father had passed away the year prior to her joining the mock trial team. Over the course of her involvement, Bernstein witnessed unimaginable growth, which culminated in a top-notch performance at the state competition of her senior year.

“Her mother took my arm [after the competition], and she had tears in her eyes. She said, ‘I just wish her father could see her now,'” Bernstein

said. “I see her mother from time to time, and of course her daughter’s a grown woman now. Her mother loves to tell me how successful she is, and I think if there had not been mock trial or something like it, she would still be hiding in the back of the room.”

But despite his ability to continue such a legacy, Bernstein recognized that it was time for him to step down. The reins will be passed on to former

White Station mock trialer and current assistant coach Mark Erksine.

“White Station’s is an elite mock trial program, and Mark is an elite coach. I’m not going to find another elite coach to take it over,” Bernstein

said. “I just felt like this was an opportunity that was not going to come along again, and I don’t want this terrific program we’ve worked so hard to build to die.”

Donate to White Station Scroll

$610

$500

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of White Station High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.