Dylan Bolden (12) stands behind the line of scrimmage, sweat dripping across his face, with blinding stadium lights shining upon him. He has been taking down offensive players as a linebacker since he was five years old and has ambitions of doing it for the rest of his life. He clenches his fists, and the veins on his forearms pop under a dark, ink etching of a tattoo.

Toward his bicep, there is a sun emitting rays downward all the way to his wrists, where a cross stands tall above a rose’s ruffled and delicate petals. Under that are the roman numerals XII/XV/XXII, signifying the date of his father’s death.

“He played a big role [in my life],” Bolden said. “He’s the best dad I could have. [He’s the] only dad I could have, really.”

After his father’s shocking death in his sophomore year, Bolden frequently missed school. Keeping up his grades and maintaining a social life became difficult, but he never quit football. Bolden got the tattoo last year under his sister’s guidance. He decided to dedicate it to the two things that were most important to him and drove him while playing: religion and his father.

“It threw me off, because I never expected it,” Bolden said. “It messed me up. But now, it just pushes me to do better. It was always my dream to make it to the NFL [National Football League], so I had a big reason to come back.”

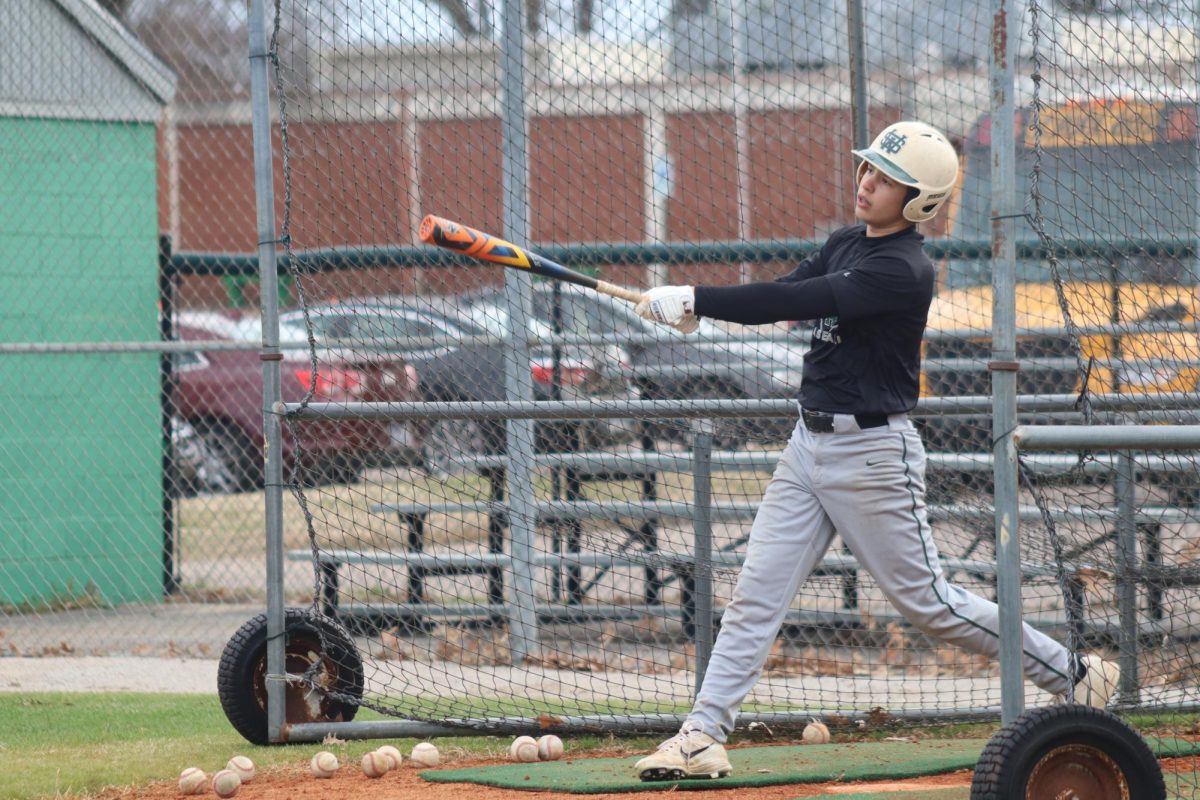

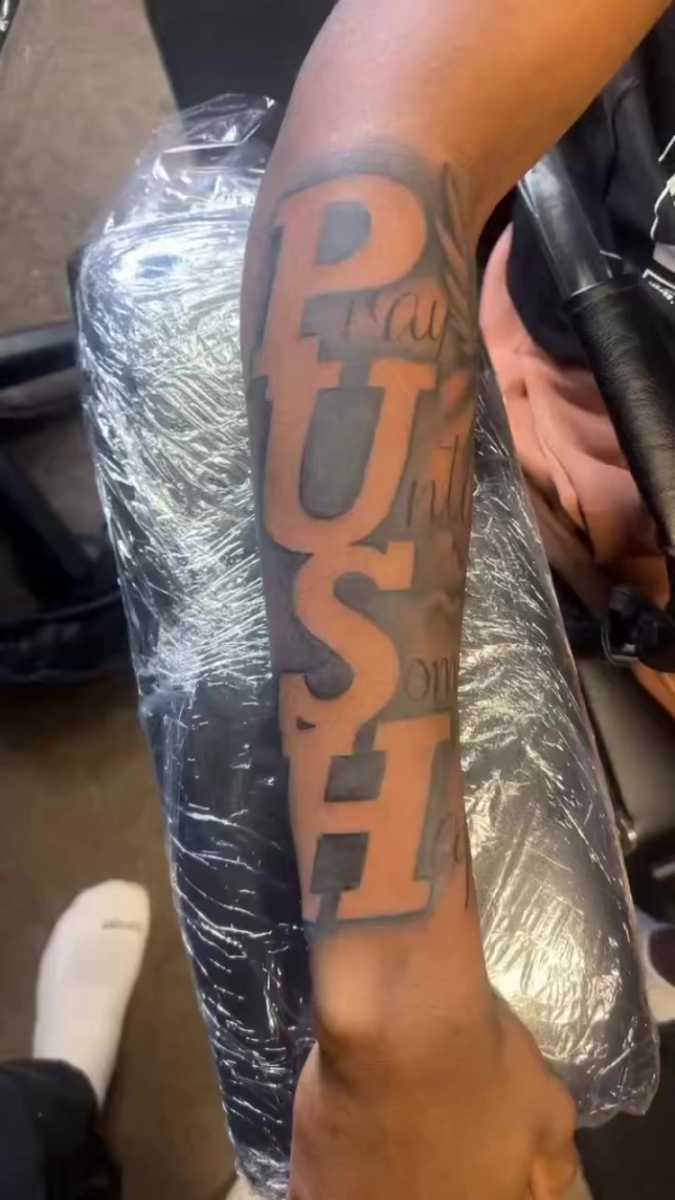

Bolden hasn’t been the only athlete to dedicate his skin to his faith and family. Demarcus Covington (12) has been playing baseball since he was 4 years old, with dreams of playing in college. Similar to Bolden, he has a tattoo dedicated to his faith that features the mantra ‘pray until something happens.’

“To be honest, I just think about my family [while I’m playing],” Covington said. “I always wanted to be the ‘him’ in the family, the guy who brings everyone together, and to be the first one who makes it. My brother graduated college, he was the first one to graduate in the family. I want to be the first person to be successful in sports in the family.”

Covington had wanted a tattoo since he was a child, and last year he finally got one. The tattoo is inked on his forearm, with praying hands, beads and an acronym that stands for ‘pray until something happens.’

“When I was eight or nine, I used to just get fake tattoos at the fair, and I knew my dad had a lot of tattoos,” Covington said. “When I got older I just wanted to get one. [I wanted the message] just keep going as far as you can until you reach your goals.”

The decision to get a tattoo is special and monumental — it is a permanent marking to be seen by everyone until, in most cases, death. Tattoos hold an especially special place for athletes, who frequently have spectators, fans, and opposition watching them closely. For an athlete with dreams of playing for life, to get a tattoo is to send a message to fans and opponents, future and current.

“I love sports, I love hitting [in football],” Bolden said. “It also just brings people together into a group. You become brothers and build a family.”