Defining moments: Life with epilepsy

A Memphis Conversation story on Grace Hugueley: http://amemphisconversation.com/2013/12/15/amazing-grace-understanding-epilepsy-a-first-person-perspective/

“I didn’t even have the hear the word ‘seizure.’ I had that feeling where all my blood rushed to my fingers.”

One moment senior Grace Hugueley was sitting the library; the next, she was witnessing a fellow White Station student convulse and collapse to the floor. Although Hugueley, an epileptic for nearly half of her life, would quickly rush to help, she couldn’t help but think, “Oh, that’s what a seizure looks like.”

At age eleven, Hugueley began to experience frequent headaches and stomach pains. Her mother, a practicing nurse, thought she was simply having “growing pains.” But the aches soon grew worse. Hugueley went to several doctors, but not one could pinpoint the exact problem.

“At first I thought, ‘Oh, this is normal. Everyone goes through this,'” said Hugueley.

But only a short time later, Hugueley endured her first grand mal seizure, the most common and most dramatic type. She was sent to Le Bonheur Hospital, where she was diagnosed with epilepsy.

Those growing pains, Hugueley learned, were actually a mild type of seizure known as focal seizures. “So many doctors, even the migraine specialist [I went to], didn’t recognize it,” she said. “It’s not anybody’s fault. It’s just that a lot of doctors in America don’t know a lot about epilepsy and the different forms of seizures.”

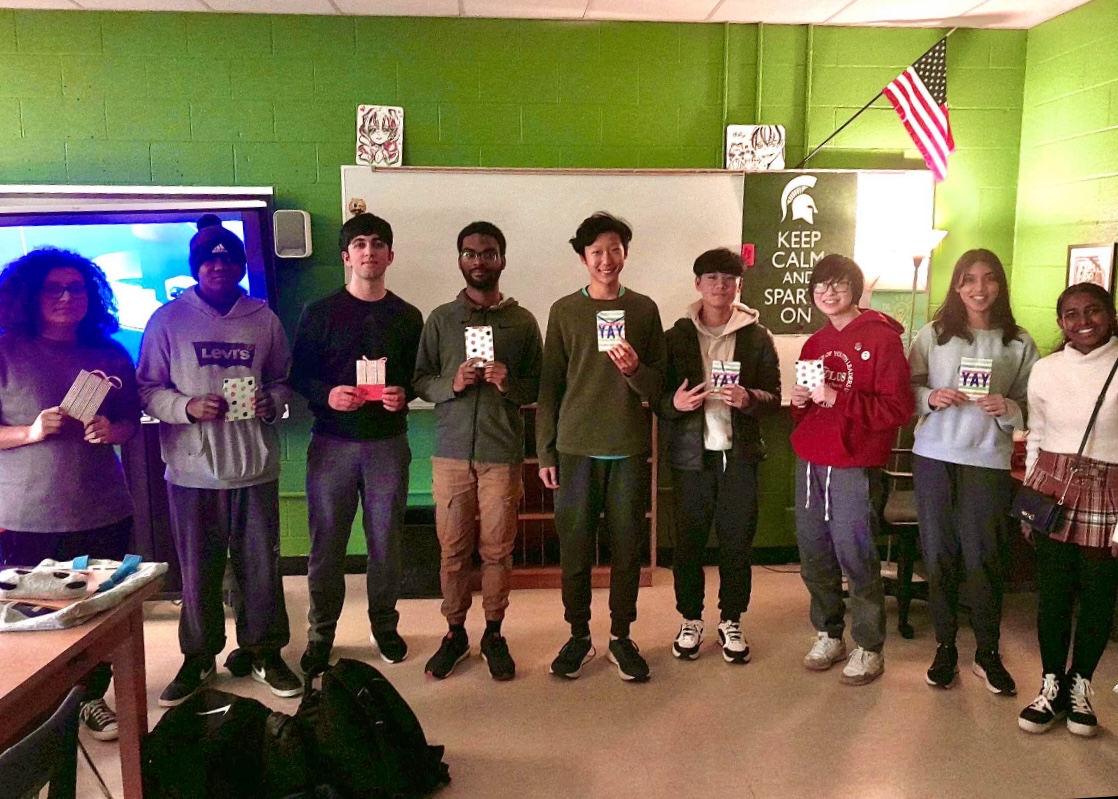

Over the years, Hugueley has learned to cope with the disorder and even uses it to help others. “One in twenty six people in the United States has epilepsy,” she said. “There are a lot of kids here [at White Station] with epilepsy that don’t talk about it.”

Educating others about epilepsy has become one of Hugueley’s top priorities. The average American doesn’t know how to deal with a seizure or what the different forms are. After witnessing that seizure during school, Huguely asked vice principal Carrye Holland for permission to speak to the faculty about the proper ways to handle seizures, both in the classroom and in public.

However, living with the condition hasn’t always been easy. “It took time,” said Hugueley. “You learn to deal with it your own way.”

Attending meetings at Le Bonheur for families affected by epilepsy has helped Huguely to cope with the disorder. She believes her positive attitude has benefitted her as well. “I joke about myself when I hear what I say after I wake up [from a seizure],” she said.

Some might think that living with epilepsy at such a young age would be a great obstacle. Yet Huguely has managed to transform her condition into an advantage.

“It’s given me a lot of joy touching peoples’ lives through [epilepsy],” said Huguely. She even plans to attend college for nursing so she can work in the epilepsy moderating unit at Le Bonheur.

“[Having epilepsy] has turned my life around. I wouldn’t change anything about it.”

How to Respond to a Seizure

Although there are multiple types of seizures, the most common and most dangerous form is known as the grand mal seizure. This type of seizure is often characterized by a loss of consciousness and muscle convulsions in the affected person. If you ever happen to witness a grand mal seizure, or any similar form, remember these steps:

Stay calm. Call an ambulance immediately, and if you know the affected person, contact a family member or guardian.

Back away. Make sure he or she is lying down on his or her back if possible. Do not try to hold the person down or touch him or her. This will only put you in danger of being hurt, and it will confuse the person when he or she wakes up.

Comfort. Once the seizure ends, allow only one or two people to interact with the affected person. Be repetitive, saying, “You just had a seizure. Everything is fine. You’re okay.” He or she will most likely be very disoriented, so your goal is to comfort and calm him or her.

Ask a question. However, only do so occasionally. Questions such as, “What year is it?” or “Who is the president?” are great. If he or she doesn’t know the answer, tell this to medical personnel once they arrive. If he or she responds correctly, no serious problems are likely to have occurred, but still tell medical personnel.

Be patient. The affected person might not respond to anyone at first. Do not worry. Continue to comfort him or her until personnel arrive.

Your donation will support the student journalists of White Station High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.