The truth about teaching

A decline in morale

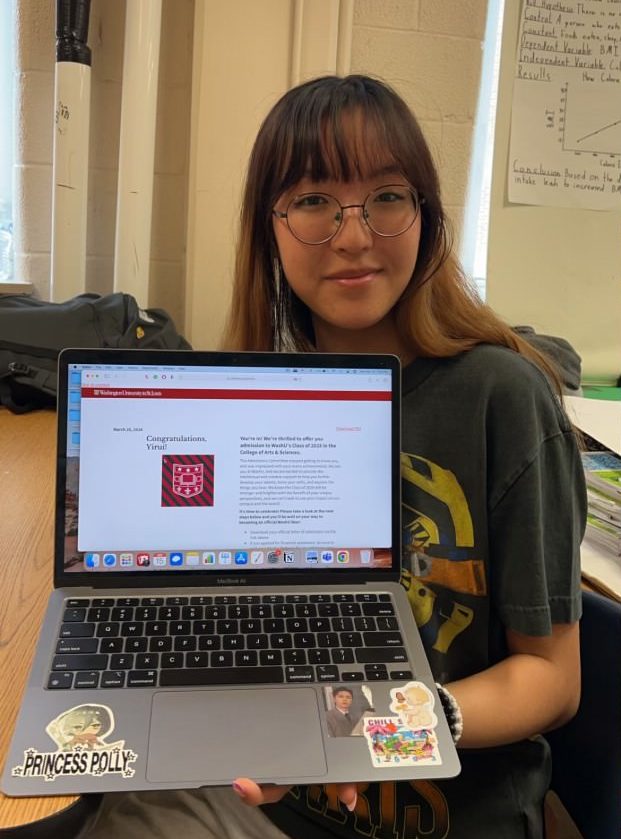

Vice Principal Carrye Holland observing new teacher Spencer Jordan

Some teachers are moms and dads to hundreds of students a day. They might provide food to the student without lunch, a hug to the one sad. Teachers can be comedians when a student needs a laugh, a therapist when a student needs advice. They start work before the average Joe wakes and then stay after for tutoring. Teachers are never off work.

And among these same teachers, morale is low.

“[If] we keep getting the respect that we are getting now, then in three years I’ll be looking to do something else,” Instructional Facilitator Terry NeSmith said.

Our teachers care. They work incredibly hard and sacrifice so much for their students. But we risk losing them to burdensome evaluations, lack of respect and inadequate pay.

“I don’t think they’ve realized what they’ve done,” art teacher Ebony Johnson said. “You’re never going to be able to keep a teacher like this. It’s just not going to happen.”

According to the Fall 2014 Teacher Insight Survey, 24 percent of teachers in this district are planning to leave this year or next. Almost one-fourth of all teachers. While some might be retiring, the lack of respect, of support, plays a part.

“I used to be trusted to be a good teacher. The administration believed in me and supported my work,” math teacher Susan Campbell said. “Now I am forced to give common assessments and report the results to my administrator. The implication is that I need help in assessing what my students know and need to learn.”

In recent years, teachers have felt more pressure as a result of new reforms. And the disconnect between the state and the district and between the district and its teachers has only increased.

The recent wave of reform in Shelby County came in 2009 when Bill and Melinda Gates donated $90 million to help improve Memphis City Schools.

Although the donation is a small percentage of the district budget, it gave the Gates Foundation the power to make sweeping changes to local education. Testing became more crucial. Salary increases became tied to scores. Teachers’ education level (except for math and science) was no longer a factor in determining pay.

“You cannot find any research that shows there’s a strong correlation between an advanced degree and student outcomes,” Governor Bill Haslam’s Chief of Staff Mark Cate said in a phone interview.

Prior to August 1, 2013, SCS teachers enjoyed a pay scale that recognized their level of education and years of experience. But the only raise local teachers can soon expect will be tied to scores, much to many teachers’ chagrin.

“I have a problem with the fact that teachers can’t be paid for advanced degrees. I have a problem with the fact that we are in the ‘business’ of education but [a teacher’s] education isn’t valued,” said Instructional Facilitator Tammie Hayes.

Along with the Gates Foundation’s donation came the Teacher Effectiveness Measure (TEM), which is used for teacher evaluations.

TEM was implemented as a result of a nation-wide research project on what makes a “good” teacher.

“At the end [of this research], I would hope that what we would have is pure, respected data. What I’m afraid we are going to have is skewed data,” NeSmith said.

“Just because you are a great entrepreneur and you have a great company doesn’t mean we should be following your lead in the area of education,” Economics teacher Jim Edelman said.

Officials at the state level hold different opinions on Gates’s authority in the education world.

“We know all about the Gateses and what they do with money and Memphis, and understand that some [people] are supportive and others are not. But we, as the Haslam administration, think that their efforts have been very important,” Cate said.

This is one disconnect. Despite teachers saying that the changes were not helping, only magnifying the disconnect, the state has continued to implement them. In fact, more changes ensued.

Following the Gates’s donation, Tennessee received $500 million from Obama’s Race to the Top (RTTT) Initiative in 2011. RTTT was established in 2009 to challenge the country to improve education, and competing states had to present a plan to the RTTT committee.

“[Tennessee and Delaware] have statewide buy-in for comprehensive plans to reform their schools. They have written new laws to support their policies. And they have demonstrated the courage, capacity and commitment to turn their ideas into practices that can improve outcomes for students,” Arne Duncan, U.S. Secretary of Education, said in a 2010 press release.

New testing procedures were implemented. New jobs were established. Administrators were given a raise. According to a source at the SCS board, RTTT money was also allocated to testing, the advanced academics office, dual enrollment and professional development. Yet all of these implementations, all of this money, had no noticeable effect.

“A lot of people have said [RTTT money] is a flop. People say it’s no good because they haven’t seen results from it,” Vice Principal Carrye Holland said.

More frequent evaluations are also a part of RTTT. Before RTTT, teachers were only evaluated about once every few years; now teachers are evaluated multiple times a year.

So what exactly does all of this—the Gates Foundation, RTTT and ensuing changes— mean for teachers and their morale?

The evaluation system and teacher payment are major concerns.

Under TEM, student testing data (or portfolios for non-tested subjects) and observations account for 90 percent of the overall evaluation score.

Thus, 50 percent of a teacher’s evaluation is often tied to student testing, commonly single End of Course Exams.

According to the Fall 2014 Insight Survey, only half of teachers in SCS feel that evaluation scores are accurate reflections of teacher effectiveness. And only 45 percent agree with the criteria of evaluations.

Another problem in analyzing testing for effectiveness is that outside factors and previous classroom experiences interferes with student performance. As a result, teachers worry about their inability to affect scores. But the district claims that it looks at growth, not just achievement. However, this does not help the teacher with a class in which most of the students are in the 90th percentile to start with. There’s only so much growth possible in those situations.

“This is education; we should be allowed to educate,” Hayes said. “The focus has gone from education; it’s more about numbers and percentages than about educating children. It’s troubling.”

Although the survey indicates a desire to revise the evaluation system, there is no denying that testing will always be a factor… and no changing the fact that students will be taken out of class to take the tests.

“We have so many interruptions and so many things that weaken the ability of my students to get a quality education that it does make it hard to keep doing it. There are certainly times when I feel like throwing up my hands,” history teacher Mike Stephenson said.

Then there’s the lack of transparency. To maintain testing security, teachers do not get to see the questions. If they did, the state would ultimately have to spend money to produce more questions. Fortunately, Cate claims that transparency is something that the Haslam Administration aims to improve.

Instructional Facilitators Terry NeSmith and Tammie Hayes looking over observation results

Observations account for another 40-50 percent of a teacher’s overall evaluation score, causing some to focus more on performing than teaching. Many teachers dread the day an observer appears at their door.

“We’ve got lots of good teachers who are fearful that they won’t score well,” NeSmith said.

Some teachers, like Stephenson, know they won’t get the highest score before an evaluator even walks in.

Stephenson lectures. Humorous accents. Flailing arms. Funny faces. He captivates his students into history.

But this style of teaching is not considered effective.

“It’s ridiculous to say that [lecturing] is an ineffective way of teaching when it’s been done for hundreds, if not thousands, of years,” Stephenson said. “What they ought to be doing is teaching effective ways to lecture.”

And Stephenson’s methods are working. His students’ AP scores are well above the national average. Yet he only made 3s and 4s on an evaluation last year.

“The problem with [the observation rubric] is that it’s too broad,” Stephenson said. He then cited the example of how his daughter, who teaches 5th grade, is evaluated on the same rubric. “And there’s a big difference between AP history and elementary.”

Note to the reader: threes and fours are not bad. In fact, Holland said, “We were taught as an observer that a three is where you want to be.”

And then there are the teachers who, rather than teaching, cut the corners just to get a higher score.

“A bad teacher can put on a dog and pony show for 45 minutes just like a good teacher can. Doesn’t mean that they are a good teacher because they can hit all of the bullets,” Campbell said.

Observations were built to be objective, but teachers are human. Subjectivity creeps in.

“The basic, same lesson plan can be scored very differently. But that goes to the competency of the administrator,” Edelman said.

The state admits that no evaluation can be 100 percent reliable. “But you also can’t wait until you have a perfect instrument,” Cate said.

According to the Fall 2014 Teacher Insight Survey, 79 percent of SCS teachers do report that they get enough feedback on their instructional practice. And even 75 percent say that this feedback does help to improve student outcomes. So there are evaluators who care and genuinely want teachers to improve.

“I’m not coming in to tear you apart. I want to see what you’re doing so that I can give you feedback to improve,” Holland said. “Without meaningful feedback, the score is arbitrary. ”

“Everybody could improve the way they are teaching, if you are having an honest conversation, equal to equal, and someone is not talking down to you,” Campbell said.

However, linking scores to pay diminishes the potential benefits of those conversations.

“What we’ve gotten away from is improving teaching; it becomes about the numbers when it’s tied to money,” Holland said.

At the end of the 2013-2014 year, SCS teachers were given bonuses dependent on their overall evaluation score. For the upcoming 2016-17 school year teachers will receive a bonus of $1200 with a 5, $1000 with a 4, and $800 with a 3. A score of 1 or 2 will not merit a bonus; however, teachers with these low scores for two consecutive years may face dismissal.

With this plan, every teacher will start at a base salary, which will increase slowly every year. But even if a teacher earns a score of 5, $1200 bonus is less than 2 percent of the current average salary.

“If they came to me and said that I was going to have to do everything on the rubric to get ‘x’ amount of dollars, I would really tell them that I’ll pay them that amount of money just to leave me alone and let me teach,” Stephenson said.

Only 56 percent of teachers feel that they can identify their own strengths and weaknesses based on the evaluation as a whole, yet Cate supports having evaluation-based pay.

In fact, starting next year, the 40,000 people that work for the state government will be paid based on performance, similar to the 1-5 scale, rather than the current across-the-board pay.

But for SCS teachers, the issue of payment runs deeper than the coming evaluation-based system.

It’s been three years since legacy MCS teachers have had a raise or a step increase.

“Now that I’m at a point where I’m looking to create a family and looking down the line towards retirement, I don’t see why I stay,” Johnson, who is leaving her job at the end of this year, said.

When asked how a lack of payment increase is possible, Mark Cate had no idea.

“I don’t see how it’s possible that they haven’t gotten a raise when we’ve put money in teacher salaries three out of the four years we’ve been in office,” Cate responded. “We’ve actually spent more money on teachers’ salaries than the president did in eight years.”

Jayme Place, an education policy analyst in Governor Haslam’s office, reported that teachers did receive a raise. And she is right. But not all teachers did.

“We didn’t [give money to legacy MCS teachers] last year, because when the two merged, MCS made more than SCS. And we wanted to make sure that all were equal,” Director of Human Capital at SCS Sheila Redick said.

This explains no raises in the 2013-2014 school year. But what about the previous years?

“The school district took all of that money and gave it to principals and assistant principals,” said Executive Director of Memphis-Shelby County Education Association (M-SCEA) Ken Foster.

If the money had gone directly to the teachers, teachers would have received a 3 percent increase in salary.

“My thought is if the governor says here’s 3 percent for Terry NeSmith to get a raise, then Terry NeSmith should get a 3 percent raise for his cost of living,” NeSmith said.

“I am making the exact same amount that I did four years ago when I first started working with the district,” Johnson said.

There is an obvious disconnect between the state and local level when teachers can go three years without a raise. And this is possible because the money the state gives for teacher salaries goes to the district, not directly to teachers.

“We believe that the districts should have the flexibility to use the money how they deem best,” Cate said. “We don’t prescribe specifically how they use it, but they have to report back that they used it for salaries.”This allowance has resulted in teachers not receiving even a cost of living increase for three years.

This year will be no different. Teachers will receive no cost of living increase, no step increase, and no raise. Fortunately, next year things will be different.

Governor Haslam’s proposed budget for this upcoming fiscal year sets aside $98.7 million for teacher salaries.

This could average a 4 percent pay increase for every teacher. Yet, the money will not go directly to teachers, but will again be given to individual school districts. The superintendent will then propose a way to use the money, and the proposal will go to the board for approval.

The approved proposal for the 2015-2016 year is that the SCS pay method will revert back to its old ways, and every teacher below step 18 will receive a step raise. However, the policy of tying money to evaluation scores won’t begin until 2016-2017. Shelby County Schools is attempting to strengthen the plan before implementation and avoid the backlash received last year.

The question remains: does SCS have this money, and how will they keep the promises made?

“There is money in the budget now that we’ve normalized after the merger,” Redick said.

But even if the board has the money to increase pay for teachers next year, it only begins to solve the problems, the biggest of which is the disconnect. The state believes each change it makes benefits teachers. Yet there is nothing helpful about an evaluation system that stresses teachers out, that causes teachers to loathe going to work. When teachers went three, now four years with no raise, no one listened. Teachers try to make their voices heard, yet they’re ignored. Teachers continue to leave the field. Maybe postponing the implementation of evaluation based pay until the 2016-2017 year is the board reacting to the voices. But is it just prolonging the same decision? Or will there be adjustments?

The state started implementing many of these reforms in hopes of improving the education system and of keeping great teachers. But is it working?

“We are still losing good teachers,” Holland said.

While everyone involved wants to see education improve, not everyone can be right. It’s time for the State to see the effects that portfolios, testing, observations, constant meetings and paperwork are having on teachers. Mark Cate claims that he doesn’t think teacher morale is spiraling, and he has his reasoning. But the Insight Surveys contradict this.

Teachers joined this profession because they love teaching; they love seeing a light bulb go off in a child’s mind.

“There’s no greater compliment, and its worth more than money to me, than when people come back from college and tell me that they were uber prepared,” Stephenson said.

They didn’t expect anything lucrative, and they certainly didn’t expect great pay.

But they do expect and deserve respect. Teachers deserve to feel valued. And they don’t.

Your donation will support the student journalists of White Station High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.